Will Artificial Intelligence be Nostalgic?

Artificial intelligence, in a moment of nostalgic musing, could decide to take a human body out for a spin.

In 1996, I decided to teach myself to use my parents’ turntable. They weren’t home; I was sixteen years old. I really, really wanted to listen to The White Album on vinyl. I had a version of it on cassette, but I craved the authentic experience. At the time, I believed that I related more to The White Album than my parents did. I always loved The Beatles when I was young, maybe because digging something “vintage” is part of the same emotional gymnastics involved with reading and loving science fiction.

Thinking about things outside of their regular context might be a lazy definition of sci-fi, but it isn’t wrong. But what is nostalgia—particularly the adolescent brand involved with my turntable coup, the borrowed nostalgia for a previous generation’s media—exactly? How can you love something without knowing its context? Could a super-evolved artificial intelligence decide to develop nostalgia for things it never experienced: chocolate, say, or The Beatles, or even...being organic? What if, just as I struggled to use my parents’ turntable to listen to The White Album, piggy-backing onto an experience I was too young to remember, an artificial, self-aware being of the future longed to put its consciousness inside a human-like brain and body? We saw poor Mr. Data try tackle this metaphysically on Star Trek: The Next Generation. He longed to be more human—not jealous, but more of a Pinocchio complex—and the whole crew of the Starship Enterprise indulged him in this notion. Of course, not one of those Star Trek cohorts actually thought about helping Data accomplish his goal. Pretty screwed up if you think about it: no one suggested growing a clone-style human body for his machine mind. With all the crazy stories told on Star Trek, transferring an artificial intelligence into a human body (and then watching him freak out) is a thought-experiment missed opportunity.

We're just made out of meat.

The contemporary Battlestar Galactica applies this idea in reverse. The Cylon “leader,” Brother Cavil, complains to one of his creators endlessly about how a pseudo-organic functioning body compares to an awesome data-processing machine. He rants: “I don’t want to be human! I want to see gamma rays, I want to hear x-rays, I want to smell dark matter! Do you see the absurdity of what I am? I can’t even express these things properly!” Here, an artificial intelligence is inherently limited by humanoid structures given to it by its creator. In Terry Bisson’s short story “They’re Made Out of Meat” (originally published in OMNI in 1990) super-intelligent machines discuss the absurdity of life on Earth, seeing us as no more than “talking meat.” The predominant thinking seems to be that AI would be repulsed and mystified by our meaty ways. But where does this tendency come from—to believe intelligent machines would be so indifferent towards organic life? What if, like teenagers fumbling with a record player, they thought organic life was cool and retro? When I ask Sebastian Benthall, of UC Berkeley’s School of Information, this question—if he thinks contemporary AI could become sentimental—he tells me that in many ways, an emotional reaction from programs already does happen, we just don’t call it that yet. “Why does your GPS make mistakes? Why do search engines lead you in certain directions and not others? If this were an individual, we’d call these things biases, or sentiment. But that’s because we think of ourselves as one being, when really there are a lot of biological systems cooperating with each other, but sometimes, independent of each other. AI doesn’t see itself that way.”

The human body is old school tech.

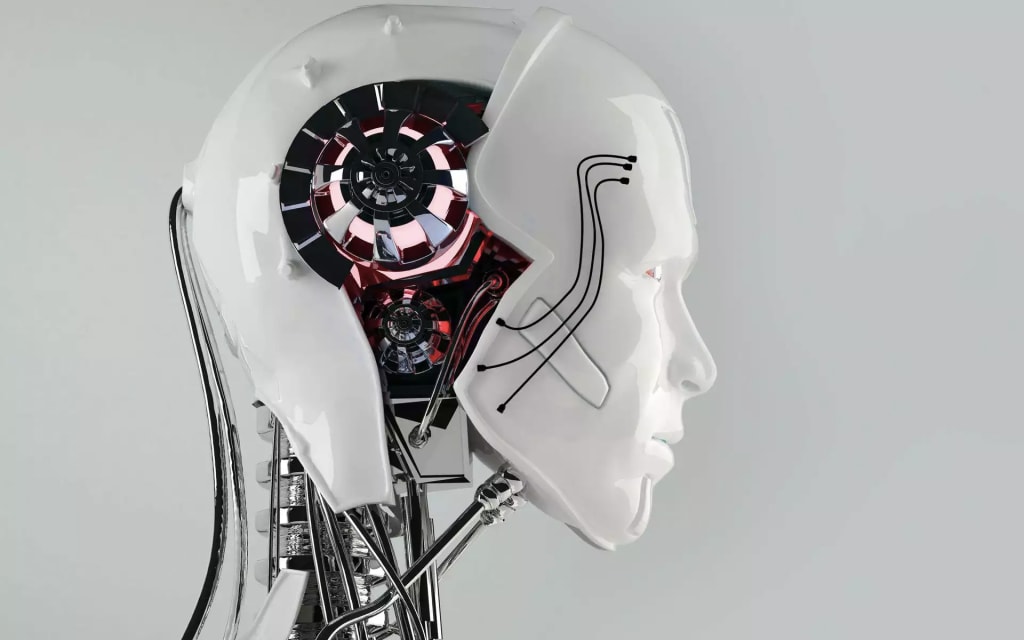

To imagine intelligent machines wanting to transfer into organic bodies requires the assumption that they'd share our sentimentality about old technology. To AI, the human body is simply vintage technology.

Ray Kurzweil, author and predictor of the Technological Singularity—that theoretical moment when artificial intelligence will finally lap the human mind—has asserted that in the future, “machines will appear to have their own free will,” and even “spiritual experiences.” Taking a cue from Isaac Asimov, he also seems to believe intelligent machines will have ethics similar to their programmers or creators. If this is true, and we were to project Kurzweil’s “Law of Accelerating Returns” forward into a future of super-evolved, super-bored robots, could one of their “spiritual experiences” include the idea of “going native,” slumming it in an organic body?

Benthall reminds me that a “brain is not like a hard drive. Information is stored differently there.” Some kind of reverse-engineering would have to be applied; though it sounds complicated, all I can think of is running my iPodthrough a tape deck in an old car. Would my future robots be all that different? To put it another way: to imagine intelligent machines wanting to transfer into organic bodies requires the assumption that they’d share our sentimentality about old technology—the human body, of course, being the ultimate old-school tech. Of course, like the hifalutin vinyl purists at the record store imposing their taste on customers, we could theoretically forcethe machines to share our fascination for all things vintage. Dr. Erin Falconer, a neuroscientist and the director of US Medical Affairs at Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, tells me that Oxytocin, essentially a love and bonding neurochemical, “may be connected to nostalgia.” I’m interested in figuring out if said chemical could be created artificially, even mathematically, and administered into an artificial brain.

There may be a genetic basis for knowledge.

“Could it be created artificially?” Dr. Falconer says, “In theory, yes. And if you showed your robot/person something vintage, or old, and then stimulated their oxytocin systems, then yes, you could maybe, create nostalgia.” I notice, not just from Dr. Falconer, but also from Benthall, that these speculations are peppered with lots of “maybes.” Most machine intelligence experts and brain scientists seem reticent to speculate about not one, but two difficult premises. To borrow a useful phrase from writing teacher of mine, conceiving my world of intelligent machines nostalgic for human bodies is sort of like “building a skyscraper from the top down.” To wit, after corresponding with the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, I was told my questions “were too outside of what they were working on, adn they didn’t feel comfortable speculating on them.” My intelligent robots with desires try on human body begin to feel more and more like the creation not of a mad scientist, but a mad science-fictionist—me. And yet, in animal life, including our own, scholarship suggests that information is stored inter-generationally; that a priori, we know, understand, and maybe even feel certain things before we really feel them. Maybe my future robots could be moving memories in a similar way. Falconer again: “I think there are competing hypotheses about how much "memory" is innate vs. acquired. There is some evidence that you can see cross-generational translation of previous learning in animals. In other words, if a mother rat learns a task, her babies are more likely to acquire the same task faster, demonstrating evidence that the babies are essentially ‘remembering’ something that their mother had previously learned. This suggests that there may be a genetic basis for previous knowledge/learning.”

What I want to do with my speculation is turn hardware into wetware, which would require some of kind of fluid simulation of both, and that seems unlikely. And yet, if I had Falconer’s artificial oxytocin stimulating my robots, maybe even before experience, then it seems like enough desire could send them in my direction. Kurzweil believes post-Singularity machines might exhibit free will—and, as they say, where there’s a will… Regardless of how the transfer is accomplished, it’s the reaction of a machine intelligence suddenly inhabiting an organic body that's the most interesting aspect of this thought experiment. Spme worry that a sudden lack of “ability to process all of the information inside of the being would probably be overwhelming.” I wonder if all of this hasn’t already happened before—in a very Galactica sort of way. After all, whenever I have an emotional breakdown, isn’t it because I too can’t process all the data? If I were a super-intelligent robot transported inside a human body, I may well just sit there and cry all day long. “When we don’t get enough dopamine, our pleasure centers change,” Falconer says. “And if a being, in theory, was suddenly denied a bunch of dopamine—or your sci-fi equivalent of it—you bet they’d have a breakdown.”

Because I’d never used it before, I nearly broke my parents’ turntable in ‘96. “Back in the USSR” played out of the giant speakers in our living room at double speed, Paul McCartney and John Lennon sounding like chipmunks as the music careened to its end far too quickly. Had I been a robot from the future, I might not have known the difference. Perhaps this was the way The Beatles sounded? Frustrated with the record, and my inability to figure out what I’d done wrong, I remember actually screaming out loud, the pleasure center of my brain clearly out of whack. This wasn’t my music, my world, my understanding. And yet, eventually, I figured it out. My hands suddenly moved over the knobs, the needle came down, and “Dear Prudence” came out perfectly, beautifully. I’d heard it before, but this felt like the first time. And I cried.

About the Creator

Ryan Britt

Published in The New York Times, The Awl, Clarkesworld, Crossed Genres, Nerve, Opium, Soon, Good, and Tor.com. Currently a consulting editor for Story Magazine.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.