The Miracles of Technology Vs. the Dark Side of Human Ambition

We live in a world that is healthy only to the extent that we dissect it with the miracles technology provides us.

On Saturday July 8th 1688, an Irish landowner sat down and composed a letter to an English doctor. The landowner’s name was William Molyneux. Ten years earlier he had married a woman named Lucy. After bearing him three children, she had become ill and was struck blind. But Molyneux’s letter to the doctor wasn't about his wife. The doctor’s name was John Locke and the letter was the first statement of a very profound neurological question. The letter asked the following:

- Imagine a man, blind from birth.

- Imagine that he is asked to hold out his hands. Into one hand a sighted person places a sphere and says "This is a sphere." A cube is placed into the blind man’s other hand and the sighted person says "This is a cube."

- Imagine the sphere and the cube are placed on a table and the blind man is invited to sit at its edge with his hands in his lap.

- Imagine that the man’s blindness is instantly cured.

- Can the man say from sight alone which object is the sphere and which is the cube?

This is an example of how important stories are to human beings.

Power of Stories

We cannot experience the world as a newly-sighted person can, but we can get an idea of what it must be like from people whose hearing has been restored with cochlear implants. The most common word used to describe the way things sound after the devices are switched on is "noise." To a person who has never heard before, the sense of hearing is so irritating that a significant percentage of those who receive the implants stop using them. But here again we run into the problem of imagining what it must be like to be different than we are. No one born with the capacity to hear can imagine giving it up and becoming deaf.

This is because we have different stories in our head compared to those in the head of someone who is deaf.

The power of stories can be demonstrated by a recent attempt to answer what eventually came to be called Molyneux’s Problem. In 2007, a doctor from MIT named Pawan Sinha went to India to cure poor children of their blindness. From the large number of children he treated, he selected five whose blindnesses were special. All had been born blind. In the eyes of four, the lenses were densely clouded by cataracts. In the fifth the outermost layer—the cornea—of both eyes was totally opaque. Each child’s ability to see was restricted to perceiving light or darkness. None of the children could distinguish objects of any kind by sight.

People whose eyes are equally impaired usually have corrective surgery done one eye at a time. Each of the children had one eye restored to sight and, after no more than 48 hours, Sinha performed the experiment with them. A child was shown a very large drawing of two pairs of Legos. At the same time, one of the pairs represented in the drawing was placed in the child’s hands. The child was then asked to point to the pair of drawn Legos that matched the pair in their hands.

All the children did terribly. By Sinha’s count, they were correct only slightly more often than if they had simply guessed.

This is because none of the children knew what they were looking at. Because a person who has had their blindness cured may be able to see, but sight is more than that. Sight is knowing how to look, and none of these children had ever learned.

Sinha did follow-up tests. These showed that in a matter of days, during which the children did nothing but exist, their ability to match the Legos placed in their hands with those on a drawing put in front of them leapt by a factor of 10.

The children had learned the story of how to relate the things their hands felt with the things their eyes saw. With no help. Simply by being in the world, they had learned to order its confusion and to see objects instead of noise. At the most fundamental level, this is what stories do for human beings.

Why do babies cry so much? Nobody asks this question, because as we grow from children into adults we forget that babies are what we would be without the stories that comfort us. Babies are sheaves of nerves that protrude into bedlam. These nerves are constantly raked raw by a sensory chaos to which no shape can be given. Babies are tortured for years by the mindless and meaningless precision of what their senses report. Think about the last time you broke down into tears of frustration. That bottomless well of confusion and shame that fills and overflows down your face when the world makes no sense. That was all of us for at least ten years. It still is sometimes.

Manipulating Stories

In 1929, Ludwig Wittgenstein found himself staring at a baby as it cried and thought—"Anyone who listens to a child’s crying with understanding will know that psychic forces, terrible forces, sleep within [children], different from anything commonly assumed. Profound rage & pain & lust for destruction."

In this sense babies have something in common with the mentally ill: both of them are just like us, only moreso.

The stories in our head create a world from the sensory din in which our bodies are immersed. And this need for stories, a need for something that can crystallize meaning out of noise, is felt by every level of our existence. Indeed, sometimes the need to square off chaos by telling a story becomes so powerful that the stories end up escaping our minds and telling us instead.

Two good examples of this are nuclear weapons and science.

Nuclear weapons exist because of a story we told ourselves during the Second World War. One group of people looked at Hitler’s Germany and Imperial Japan and became convinced that they were so brutal, so remorseless, so fanatical, that only indiscriminate death and unbridled power could subdue them. How many people were evaporated by the light of those weapons because of that story’s usefulness?

And being what we are—animals who spend our formative years subjected to unimaginable torture and confusion—we quickly discovered the profit in manipulating the power of stories. A Japanese empire was built on the strength of a story about its racial superiority. Later, millions of white people were made not only to accept, but even applaud (as at the end of a play) the annihilation of two fully populated Japanese cities. Because their story’s conclusion could not be reached in any other way.

Stories Told by Science

Science is a story, too. Or rather, a series of stories that permit us to understand the octaves of sensation far above and far below the grasp of our own nerves. The theory of gravitation is much the same as a newly-sighted child learning how to connect a shape they feel with an object they see. If we could look much more closely at our own skin, we would see the innumerable and identical objects that compose it. "Science" is the story in which those objects become cells, just as "seeing" is the story in which a confusing visual sensation becomes the Lego you hold in your hands.

But as soon as we get out of our heads and into the world, our stories become complicated. They can be manipulated by the wealthy and powerful for their own benefit, or simply pruned back to make them easier to understand. A good way of seeing this last one is the difficult and incomplete birth of modern science out of what came before.

For example:

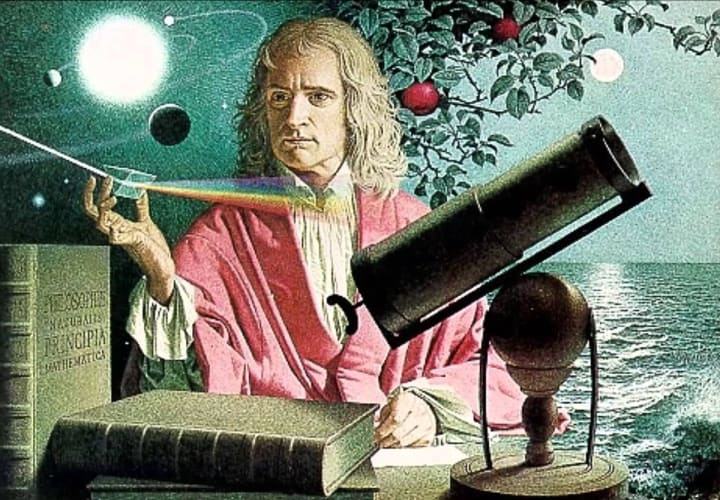

From 1779 to 1785, an English bishop called Samuel Horsley brought out five very large volumes of Isaac Newton’s complete works. The series was called Isaaci Newtoni Opera quae extant Omnia ("Everything that Exists of Isaac Newton’s Works"). This was the first time Newton’s works had ever been collected and it included the books that you’d expect to find, things like his Opticks and the Principia, along with lesser known things like Newton’s commentaries on the Temple of Solomon and his interpretation of the Book of Revelations. What Horsley’s edition notably did not include, and which in length far outnumbered everything Newton ever published, were his magical writings. Horsley didn’t think it seemly to publish what amounted to number mysticism and alchemy alongside the most important works of Enlightenment science. And so he simply put them in a drawer. One hundred and fifty years later in 1936, Newton’s mystical and alchemical writings reemerged at Sotheby’s in London, where they were bought by the economist John Maynard Keynes.

Keynes had eagerly collected Newton’s occult manuscripts all his life and he stated the situation in a very stark way. He said that Newton “was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians."

This is important because scientists and magicians seem to tell very different stories about the world. The stories that science tells are meant to interlock with each other, like Legos. Every scientific story has certain features in common with every other scientific story. These features, like the use of mathematics or logic or the conceit that matter is atomic, allow explicit connections to be made between them, even if their subjects are widely separated. This availability for interconnection is one of the things that makes science a powerful force in our world.

Darker Sides of Human Ambition

The stories that magicians tell would seem to be very different. The word occult means "hidden;" this tends to describe the types of stories whose logic is not readily apparent. However, the important thing to remember is not that magical stories "don’t make sense" or that alchemy "doesn’t work," but that Newton thought they did. This primordial connection between science and magic in a person like Newton allows us to tell a more interesting story about science than we otherwise might.

This story is that the occult is still present in science, and not in a shallow sense either. The act of connecting one scientific story to another, as when the connection between a falling apple and the moon is made, is an occult activity. This doesn’t mean that it is magical in the superficial sense of violating physical law, but magical in the deep sense that Newton believed the world to be. Which is to say, existing in a way that can be narrated by our stories up to a point, and not at all thereafter.

“There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical.” I think that Wittgenstein would have had a lot to say to Newton. And that both of them would have immediately grasped the mystical element at work in being able to recognize a sphere simply by looking at it.

The first OMNI magazine told a very nice story about the progress of science. This story braided the innumerable threads of scientific advance into a rope. One end of which was anchored in the present as the rest of it stretched out into the future. Where Captain Picard held the other end. And all we needed to do, the magazine said, was climb.

The first OMNI I ever read was the topmost issue in a stack kept on a bedside table. The stack was in the guest bedroom of the Boston townhouse next to the one I grew up in. The subscriber was a woman I call my godmother, because that’s the only easy way of describing her relationship to me. She was and is a computer programmer, whose first job out of MIT was helping Raytheon make the Apollo Guidance Computer. On top of the stack of OMNIs was the remote control for a Zenith set so old that the remote’s hard, plastic buttons made a loud click when you pressed them. Whenever my parents were out of town, that guest bedroom and that stack of OMNIs were where I went.

To me, OMNI, The Next Generation, and Jacob Bronowski were the things that crystallized what science was for. Getting off this rock.

I still want badly for Picard to be on the other end of that rope, but I think we’ll be bringing a number of things with us as we climb it. Not least of which is our reliance on stories. And so also our weakness, when those stories are exploited.

My point here is that as technology becomes more and more miraculous, and asymptotically approaches anything Gene Roddenberry imagined, I think that we will have to know ourselves in deeper and deeper ways in order to remain human.

Otherwise, the future is just going to be another stage set, on which the darker sides of human ambition will play its plays. And the stories we need but do not understand will tell us instead. Making sure we stay Earth-bound and blind—even to the objects we hold in our own hands.

Like always.

About the Creator

George Lazenby

Unauthorized pseudonym of someone who became accidentally famous on Twitter. He is a contributor for OMNI when not unlocking the secrets of the universe.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.