Origin of Star Trek

Gene Roddenberry reveals the tough times Star Trek, The Original Series, faced in its early days.

Author Marc Cushman’s first installment of his These Are the Voyages, an exhaustive three-volume set devoted to the making of the original Star Trek television series, was published by the boutique imprint Jacobs Brown Press. From the nondescript cover you'd never know this book is any different from the hundreds of other books about Star Trek that have lined bookstore shelves and digital libraries for decades. However, after reading only a few pages, it will become abundantly clear that this is a book like none ever published about the making of Star Trek or any television series, for that matter.

Having begun writing his trilogy back in the early 80s with the blessing of the great bird of the galaxy himself, Gene Roddenberry, Cushman mined the rich archival material available from the Roddenberry and Robert Justman collections at the UCLA Film & Television archive to explore the making of every individual episode relying on the original network notes, call sheets, budgets, ratings and early drafts of each shooting script. As a result, Cushman has unearthed and assembled a treasure trove of unknown information about the series, debunked many accepted myths and provided fresh insight into a series that has been chronicled and analyzed for decades.

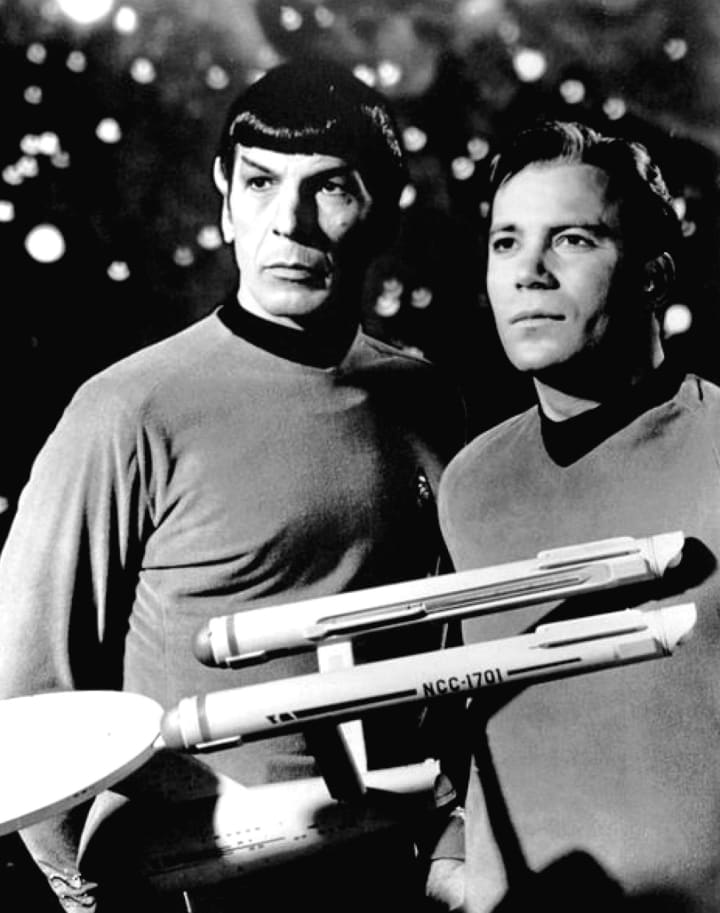

In the following excerpt, the author takes a look at the making of one of the second season's most popular episodes, "Who Mourns for Adonais," in which the Enterprise is seized by a giant hand in space, only to discover that a powerful entity on the planet below calls himself Apollo. The Olympian deity, once worshipped on Earth by the ancient Greeks, is now looking for a little love and adulation from the crew of the NCC-1701.

In addition to exploring the many challenges of making the episode, the author also explores the lost "Rape of the Wind" sequence, in which Carolyn Palamas is taken by Apollo and is revealed to be pregnant in a coda, excised from the final shooting script. For any Trek fan, all three volumes of These Are the Voyages will be essential reads.

"Who Mourns For Adonais?"

Production Diary - Filmed May 31, June 1, 2, 5, 6, 7 & 8, 1967 (Planned as 6-day production, running one day over; total cost: $203,623).

Filming began on the last day of May 1967, immediately following the Memorial Day holiday (falling on Tuesday in those days, not Mondays). "More of the Monkees" was still America's best selling record album, now in its 16th week at the top. On the Billboard singles charts, Aretha Franklin moved to No. 1 with "Respect", nudging out "Groovin" by The Young Rascals. CBS was the top-rated network from the night before with Daktari and The Red Skelton Hour. Red's guests were Ozzie and Harriet Nelson and singer Barbara McNair. In the movie houses, and selling the most tickets (at $1.25 each), was The War Wagon, starring John Wayne and Kirk Douglas.

A letter in the current issue of TV Guide, addressed to Cleveland Amory, the resident critic, said:

"Dear Mr. Amory. Don't feel bad. In the next few days you're going to get 5,227 letters of protest about your review of Star Trek, mentioning your 'total inanity' [Sic] and 'bad puns.' Now there are only 5,226 to go."

The writer was one Rae Ladore. Amory had since reassessed Star Trek and decided that he liked the series after all.

Day 1, Wednesday, May 31, 1967

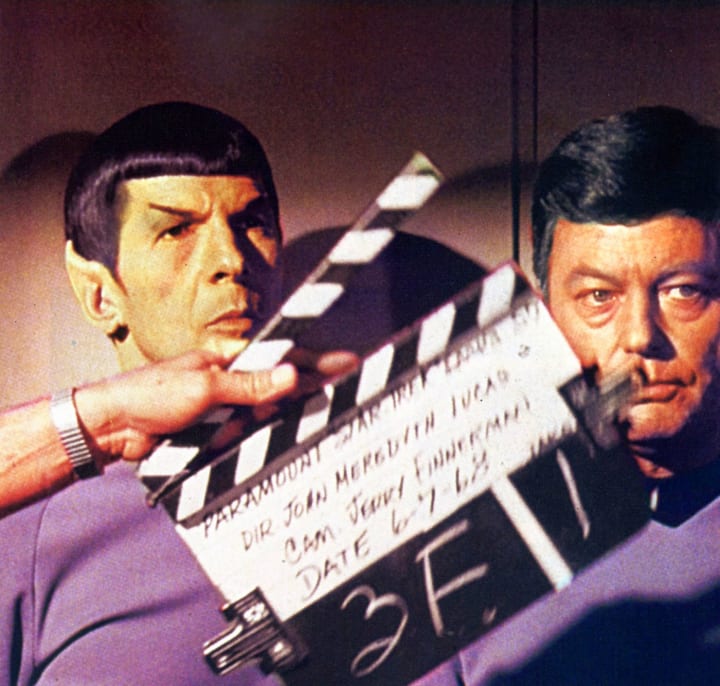

The start of filming for "Who Mourns for Adonais?" was typical of every episode of Star Trek. Fred Phillips and his makeup department had a 6:15 AM call time. Both Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner arrived at 6:30; Leonard for his ear job, Shatner for his hair. And Nichelle Nichols was there at 6:30, as well, for her hair and makeup. The second assistant director (2nd A.D.) was there to take breakfast orders. The remaining male players were given an extra half-hour to get to the studio. The camera and lighting crew arrived at 7 AM to begin preparing the set. Also reporting to work at 7 AM were the property man, sound men, costumers, assistant director, and director Marc Daniels. The sound mixer and camera operator were given a little more time to wake up. Their call time was 7:30.

The entire day was spent on the Stage 9 bridge set. Jerry Finnerman was out sick this first day and replaced by Arch Dalzell. The 45-year-old cinematographer was the D.P. for the 1960 cult film Little Shop of Horrors, as well as the television shows The Rebel, Mister Ed, and The Addams Family. The title song for The Addams Family may have told us "they're creepy and they're spooky," but the scenes Dalzell lit and shot on the bridge were not quite as shadowy as those done by Finnerman. In the teaser, note the elevator doors behind Kirk as one example. They are lit both bright and flat, instead of with textured shadow patterns at the top, as Finnerman always did.

Leslie Parrish was noticing the lighting, but more so the blinking ones coming from the bridge computers. She said, "That bridge set was pretty awesome. I loved the computers. We didn't have them than for personal use. But when they came out, I was one of the first to get one. The future has always been much more real to me than the present. So when I walked into Star Trek, I felt I was at home. I thought this is the way it ought to be. Not just with the computers, but with the people—the way they were portrayed, in a time when it didn't matter what race you were or where you were from. The ideals and values were marvelous. It had Gene [Roddenberry] all over it–his values. I just loved him. I felt a kindred soul with him."

Day 2, Thursday, June 1, 1967

The Beatles released Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. To no one's surprise, it was awarded a Gold Record certificate before it even got into the stores. Meanwhile, another full day was spent on the bridge of the Enterprise. Finnerman had returned, bringing his cinematic dark tones and shadows back to the show.

One bridge sequence planned for this day was not filmed—the episode's "tag scene." Writer Gilbert Ralston had been daring in ending the story with the discovery that Carolyn Palamas, after her time alone with Apollo on the planet, was now pregnant. The creative staff loved this idea and kept it in the Script. NBC's Jean Messerschmidt was trying to be cooperative with the Star Trek producers; she knew how vital the plot point was. But, as production neared, word of the controversial subject matter began to spread to other departments beyond that of Broadcast Standards.

"The network absolutely would not allow that," Star Trek script consultant Dorothy C. Fontana said. "Oh my God, intercourse outside marriage! Usually we could sneak by a lot of stuff, but it was ultimately stricken."

The twist ending, which would have made "Adonais" one of Star Trek's most talked-about episodes for decades, was in every draft of the script, including the 2nd Revised Final Draft, from May 29, 1967. Two days later, as the scene was about to go before the cameras, revised script pages were delivered to cast and crew. The controversial ending had been removed.

The scene, tragically lost, had Spock and Kirk in conference at the command chair. McCoy enters from behind them, looking somewhat bemused. Kirk says, "Yes, Bones?"

McCoy begins, "I'm used to interesting problems...but I've just been confronted with a brand new one. Carolyn Palamas became slightly ill at breakfast this morning... I just finished examining her. She's pregnant."

Kirk and Spock react in surprise. McCoy says, "You heard me."

"Apollo?" Kirk asks.

"Apollo–positively," McCoy answers."Now I'll give you an interesting question to chew on. What will the child be? Man...or god?"

Even Spock is at a loss for words. Kirk stares back at McCoy as we FADE OUT.

With one less scene to shoot, the company broke early and cast and crew were sent home in time to relax in front of the TVs for the NBC repeat broadcast of the Star Trek first season episode "Charlie X."

Day 3, Friday, June 2, 1967

The company worked on Desilu Stage 10 and the impressive temple set. The original plan was to shoot this on the backlot but, due to all the various effects required, including a violent rainstorm, Robert Justman was opposed to the notion. The associate producer wrote Gene Coon:

"These sequences will have to be setup on a soundstage. As presently written, with the light changes and the wind and the lightning and the opticals, we have absolutely no control Unless it is done inside. Incidentally, why does it have to start raining? The answer is that it does not have to start raining."

The rain was cancelled, saving both time and money. And then set designer Matt Jefferies built as much of Mount Olympus on to Stage 10 as Star Trek's budget could provide for.

Michael Forest, cast as Apollo, recalled, "When I saw the temple, thought, 'Hey, it's pretty impressive.' I remember sitting up there on that throne while they were lighting me, thinking, 'Well, this is kind of interesting, because, in terms of the actor approaching a role, you begin to feel like that person you're portraying. You're affected by the physical surroundings—in this case, the throne and the columns."

The scenes planned for this first day were the landing party's first encounter with Apollo, them reacting to him growing taller for the first time, Apollo changing Carolyn's uniform for an ancient Greek-era gown, and Scotty getting slapped away when he charges the angry "god." But Marc Daniels, Star Trek's fastest director, with a well-earned reputation for staying on Schedule and covering an average of 10 script pages each day, was falling behind. Filming the scenes where Apollo grows to the size of a giant, dwarfing the Enterprise party, and requiring crane shots as well as numerous other camera tricks, was taking longer than anticipated. The slap that would send Scotty flying through the air had to be put off until the next day.

Day 4, Monday, June 5, 1967

There were some long faces on set this day. The Emmy awards took place over the weekend. Star Trek, nominated for more awards than any other science-fiction series in the history of television, including Best Drama Series and Best Supporting Actor (Nimoy), came away empty handed. You couldn't tell by watching the scenes shot on this day. When the camera was rolling, the series cast members put aside their disappointment and rose to the challenge.

Jay Jones, doubling for James Doohan, finally received the slap from Apollo which had him doing a back flip. And this landed Jones in the hospital with a concussion.

A second stunt requiring Jones had been planned for this day. It would have to wait until it was known if the stuntman, who was a good match for Doohan, could even return. The schedule was revised, allowing different sequences to be filmed in front of the temple.

There was further drama on the set this day. Michael Forest recalled, "When we were shooting that, that was the week of the Six Day War in Israel [June 5-10, 1967]. Everybody had their little portable radios tucked to their ear listening to what was going on. The whole week we were filming, that war was happening." Director Daniels finished a full half-day behind.

Day 5, Tuesday, June 6, 1967

Jay Jones, due to his injury, was unable to work. James Doohan was insistent he could do the second stunt required, when Apollo blasts Scotty with a lightning bolt, hurling him backwards.

“I had to talk them into letting me do the fly-back." Doohan said. "I had a harness on under my red shirt. They pulled me back when [Apollo] zapped me. I practically flew backwards, and if there hadn't been other stunt guys there to catch me, I might've gone through a back wall."

Day 6, Wednesday, June 7, 1967

Work continued on Stage 10. More dialogue was covered between Kirk and his landing team and Apollo. And then came the dramatic climactic scene where the temple is struck by phaser fire and a distraught Apollo aims lightning bolts toward the sky and the orbiting Enterprise.

The numerous camera tie-down shots, as animated lightning bolts (to be added during postproduction) were taken, turned out to be time-consuming. Daniels was three-quarters of a day behind When the camera stopped rolling, well into time-and-a-half overtime pay.

Day 7, Thursday, June 8, 1967 -- An Unplanned Day of Production

The temple set on Stage 10 had been given a makeover during the night by Matt Jefferies and his team. It was now a charred ruin. Apollo's farewell speech was filmed with him "spreading himself to the wind" and vanishing, as Carolyn Palamas weeps.

"The sadness of these characters, it was Vivid," Leslie Parrish Said. "The feelings that we had were so honest and that intense, never considered myself a method actor but, when I got something like this, I just poUred my heart and soul into it. For an actress, it was a beautiful, beautiful opportunity. But the tragedy of it really struck me. And I felt that they loved each other. And the decision of what we [the Enterprise crew] decided to do in the end was the right one, but just agonizing. It was painful to me. In our last scene together— Michael and me—we were crying. I was crying because of what had done to him. And he was crying because it was being done to him. And after, we were really crying."

Walter Koenig said, "I think Michael Forest is a terrific actor. He was actually perfect in that role. Great presence...and great resonance, too. So you believe the god-like figure. But what made it for me was the vulnerability of that character. Even though Apollo is this massive man that is used to giving orders, he is tragically needy.”

When the lunch break came, the regular cast members were dismissed; only Forest and Parrish were needed for the remaining scenes. Pevney continued on a different part of Stage 10 for the scenes where Apollo and Carolyn talk privately in the garden area. The production schedule identified the final of these sequences as "Rape of the Wind."

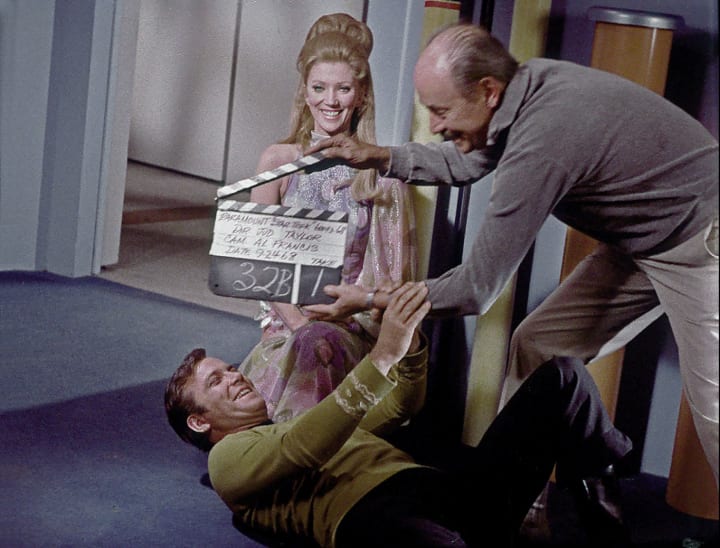

Leslie Parrish's gown was the subject of great concern during the entire shoot, but especially on this day. James Doohan fondly recalled, "She was absolutely lovely, and can tell you that a lot of sticky glue went into keeping her costume together."

"A breathtakingly beautiful girl in one of my favorite scripts," said costume designer William Theiss. “I felt this design, while Greek in feeling, was a completely fresh idea —the front of the dress was held up by the weight of the train which fell over the shoulder to the floor."

Parrish said, "I especially loved Bill Theiss for that crazy gown. What happened is he threw a bolt of cloth over me—this beautiful cloth—and just pinned it at my waist and said, "There, that's your costume. The weight of it held it over my shoulder."

"Ahh, the gown," said Dorothy Fontana. "The Theiss theory of titillation was that you could show a lot of basically non-sexual flesh, like the back, the side of the leg, bare arms, bare shoulders, skimpy in those areas, and people would be waiting for the dress to fall. But, of course, Bill made sure the outfit never did fall... well, sort of. The weight of the cape over her one shoulder kind of held the front of the dress up—so that was okay if she was just moving easily—but when she had to be throwing herself on the ground, rolling around, she had to be glued into that thing."

Walter Koenig said, "What made the episode for me was Leslie Parrish. I was on the set with her and she was glued into that costume, literally. And my tongue was hanging out, to have someone that close, and that beautiful, with that skin and that body. My god, just striking. I was praying that that gown would get caught on something and come right off. But no!" Costumer Andrea Weaver said, "It's true. Leslie Parrish's costume was glued onto her. Now we use a material which has two-sided Scotch tape; very strong Scotch tape, but then we didn't have that: all we had was glue. So the clothes that needed to be attached were glued on. And after three or four days that can get hard on the skin."

Parrish said, "There was one little section, yes, they had to glue it to me everyday. And it was a different piece of skin everyday—and everyday they'd rip it off and there went my skin and, finally, I didn't have much skin to glue it to. It was really painful."

Regarding the "Rape of the Wind," Parrish added, "That was a really, really violent scene—it was hard to do. The fan was a monster. They don't even call it a fan. They have another name for it. It was like 10 feet [round]. It was huge. And I think there were three of them. I mean, I was taking a pounding. It was hard to stay together—that gown just didn't want to stay on. At that point, it was too much to ask of a gown like that."

Fontana added, "Jean Messerschmidt, who was our Broadcast Standards person, would usually nearly have a heart attack every time she'd see a Bill Theiss' gown, or a costume that almost made it at covering the girl."

Roddenberry said, “How much skin [we were] permitted to show used to be almost a matter of geometry and measurement. I remember doing shows that showed the inside of a woman's leg. Those shows were turned down because, for some reason, the inside of the leg was considered vulgar."

Michael Forest said, "In those days you had to be careful—the censors were very strict, you couldn't do certain things. In fact, you won't believe this, but I had to take the hair off my chest, because, evidently, gods do not have hair on their chests. I've never seen a real god. Have you? I don't know what they have. But, apparently, it's not hair."

At the end of the day, Forest, cleanly shaved, was the only cast member needed. The blue screen shots were taken where Apollo, as a giant, looks down on the landing party personnel, and his disembodied head talks from Space, and his disembodied hand grabs the Enterprise.

Forest said, "I hadn't done anything with those type of effects. Most of the stuff I was doing at that time was a lot of cops and robbers, cowboy stuff, and mystery stuff. This really was special. But one of the things that was difficult was when they put me up against the blue screen. I was supposed to become taller. I guess I was up on some kind of a pedestal. But I had never been up against a blue screen like that one and I didn't know quite what to do. They said, 'Just stand there and look down, and I thought, 'Well, okay, they obviously know more about technical aspects of this than I do, and I can trust them.' But it was funny doing that, not knowing how it was going to come together."

Marc Daniels finally wrapped, one day behind schedule and deep into union overtime. Leslie Parrish said, "The six-day schedules were difficult. We did work late. I remember the last scene we shot was like at 10 or 11 at night. But nobody cared. Everybody was so into it. It was joyous doing that. There were some sets [on other shows] where it was more like work. But I loved going there."

Forest, who had worked a total of five days, recalled the Star Trek set as being a friendly one. Marc Daniels was "likable and professional," as were his fellow actors. Leslie Parrish concurred, saying, "Marc Daniels was a gentle director. I think he was a compassionate director. He spoke to you softly. He made his contributions that way."

Of Parrish, Michael Forest said, "Leslie was a delightful person to work with, no problems, never any difficulties; we would just discuss what we were going to do and we would do it. She was excellent and very personable. William was a bit of a problem, however. You never saw me standing with him; we were always in different shots. We would be talking to one another, but we wouldn't be on camera at the same time. I'm sure that's what he stipulated—because I was so much taller."

Shatner, however, had no stipulation against standing next to the leading lady. Nor did anyone else. Leslie Parrish said, "The cast was absolutely great. James Doohan was a darling, darling man; such a sweetheart. You couldn't know him and not love him."

Marc Daniels said, "That [one] was terrific....We did that episode in six [sic] days... Six days is not very much time to do an hour show. You could barely get it done if everything went right. Well, if one element goes sour, where are you? It’s just incredible and impossible, and the miracle is that anything comes out that’s worthwhile at all."

After this final day of production, cast and crew were treated to NBC's encore airing of "Shore Leave." TV Guide signaled out the delightful episode for its coveted half-page Close Up listing and declared Star Trek the show to watch that night. Like it did many times during its first season, and contrary to what 45 years of folklore tells us, Star Trek won its time slot. According to A.C. Nielsen, 31.4 percent of the TV sets running in America were tuned to "Shore Leave." The estimated audience was more than 22,000,000 viewers. ABC's top-rated series, Bewitched, came in second, with 30.7 percent, and CBS trailed with 28.7 percent for its hit series, My Three Sons. The remaining 9.2 percent of the TV's in use were switched to non-network stations. Star Trek's audience share increased to 32.7 percent at 9 PM as ABC lost viewership for That Girl, down to 29 percent, and CBS saw its share of the tele-pie decrease to 23.3 percent for the network's Thursday Night Movie.

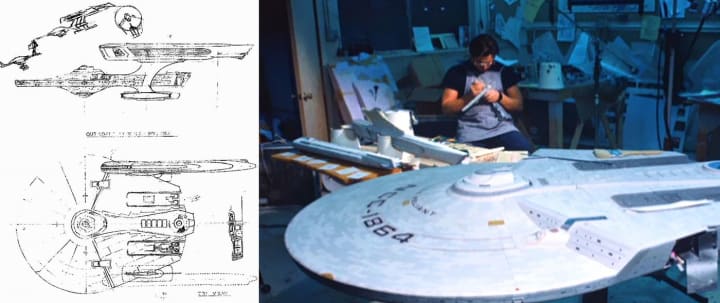

As production gave way to postproduction, Effects Unlimited provided for the photographic tricks. Their collaboration with director, editor and Star Trek's special effects man, Jim Rugg, is the reason for the success of the shot where Apollo grows to giant proportions. The result is a combination of optical effects, clever camera angles and inventive editing. Another innovative effect was the attention-grabbing image of the giant hand in space, grabbing hold of the Enterprise. This was a stunning visual for 1967 television.

Bruce Schoengarth took on his second assignment of the new season, heading up Edit Team 2. He had already cut the standout episodes "Mudd's Women," "The Naked Time," "The Squire of Gothos," and "Tomorrow is Yesterday." The camera footage was delivered to him on June 9, 1967. He finished his "rough cut," under the supervision of Marc Daniels, on June 23. The final edit, under the supervision of Bob Justman, with notes from the two Genes – Coon and Roddenberry, was completed on June 29. Clever cutting helped make all the tricks in this episode work, such as Apollo growing and Scotty getting electrified.

Fred Steiner, Robert Justman's favorite Star Trek composer, returned to the recording studio for the first of four Second Season episodes. Already to his credit: “The Corbomite Maneuver," "Mudd's Women," and "Charlie X." His work here—recorded July 12, 1967—blended new themes for Apollo with motifs from some of Steiner's earlier Trek scores.

"It's my favorite score and I think it's one of the best episodes of Star Trek," Steiner said. "It has a little bit of everything and there are some moments that I'm very fond of, particularly where I develop Captain Kirk's theme with a duet for the French horn."

The fourth episode of the season was the fourth episode to go over budget. "Who Mourns for Adonais?" came in at $20,3623, which equates to more than $1.4 million in today's currency. And this went over the mandated Desilu per-episode allowance by $23,623. Season Two's deficit was now up to $100,211 (nearly $750,000 today). The red ink was about to get darker with the next episode to film: "Amok Time.”

About the Creator

Futurism Staff

A team of space cadets making the most out of their time trapped on Earth. Help.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.