Interview With Ralph Barnaby

One of the pioneers in early aeronautics, Ralph Barnaby's legacy was influenced by many icons like Amelia Earhart and the Wright Brothers.

In October of 1910, when he was just 17 years old, Ralph Stanton Barnaby played hooky from high school and went to the Second International Gordon Bennett Air Race at Belmont Park, Long Island. His older brother was at the park, working on the engine of one of the planes entered in the race. The plane was the Baby Grand–owned and designed by Wilbur and Orville Wright. For a week before the race, young Ralph helped his brother and the Wrights put the final touches on Baby Grand.

That week was only the beginning of a career that brought Barnaby into contact with many of the great names in aviation spanning the entire 75-year history of flight from the Wright brothers to the Space Shuttle. Barnaby was friend and confidant to Orville Wright for nearly 40 years. He received flying instructions in the Navy from Leroy Grumman, of Grumman Aircraft, and through his life in aviation he came to know General Billy Mitchell, Charles Lindbergh, Admiral Richard Byrd, Amelia Earhart, and one of the pioneers of military airships, Admiral William Moffett.

But Barnaby is also a great aviator in his own right. One of the few surviving Early Birds (anyone who flew before 1916), he holds Glider Pilot's Certificate No. 1 signed by Orville Wright himself. He earned that certificate by breaking, in 1929, Orville's ten-minute soaring record, a record that had remained intact since 1911. And in 1930 he performed a stunt that paved the way for the testing of the X-15 rocket plane and the more recent Space Shuttle. In that year he climbed into a glider that was then dropped at 3000 feet from the belly of the dirigible Los Angeles. Barnaby besides capturing the front page of the rotogravure section of the New York Times, proved that a glider could be launched from a larger airborne craft and flown down to a safe conventional landing. This is precisely what was done recently with the Shuttle and earlier With the X-15.

Barnaby was born on January 21, 1893, in Meadville, Pa., but at the age of seven his family moved to New York City, where they lived in the neighborhood surrounding Columbia University. From his early days, it appeared that young Ralph would grow up to be an artist. By age 14 he had already shown artistic promise and was studying sculpture and drawing in the evenings at the Art Students League. But in 1908, after a summer of reading newspaper stories about the Wright brothers' adventures at home and abroad, 15 year-old Barnaby began experimenting with paper airplane designs. By that fall he knew for certain that aviation would be his life. But he never forsook his artistic ability. He has sculpted busts of several aviation notables, including Admiral Moffett and Amelia Earhart, and sculpted the large bronze commemorative plaque of the Wrights that now resides at Kitty Hawk.

In the summer of 1909 he designed and built a working glider and made several successful flights in it. He based the glider entirely on plans and pictures of the gliders of Otto Lilienthal, the German who was the world's first true aviator Ralph Barnaby had never seen a glider in real life.

In 1910 he met the Wrights, and after high school he attended Columbia University majoring in mechanical engineering. During that time he was active in the MOdel Aero Club, a Club that attracted many early aviators and also allowed Barnaby the chance to meet Alexander Graham Bell and Hudson Maxim (inventor of Silencers for firearms).

In 1917, after a two-year stint as an engineer for the Elco Boat Works. Barnaby entered the U.S. Navy.Though he wanted to be a flier he ended up as an airplane inspector, going to Europe during World War I to investigate parts shortages. There he uncovered a foul-up of shipping and supplying errors and even sabotage that kept American aircraft on the ground and out of the skies. After the war he remained in the Navy, eventually becoming a pilot of powered airplanes, though his first love continued to be gliders. Barnaby remained in the Navy until his retirement in 1947 and during his service instituted the Army-Navy Standardization Board, which continues to this day.

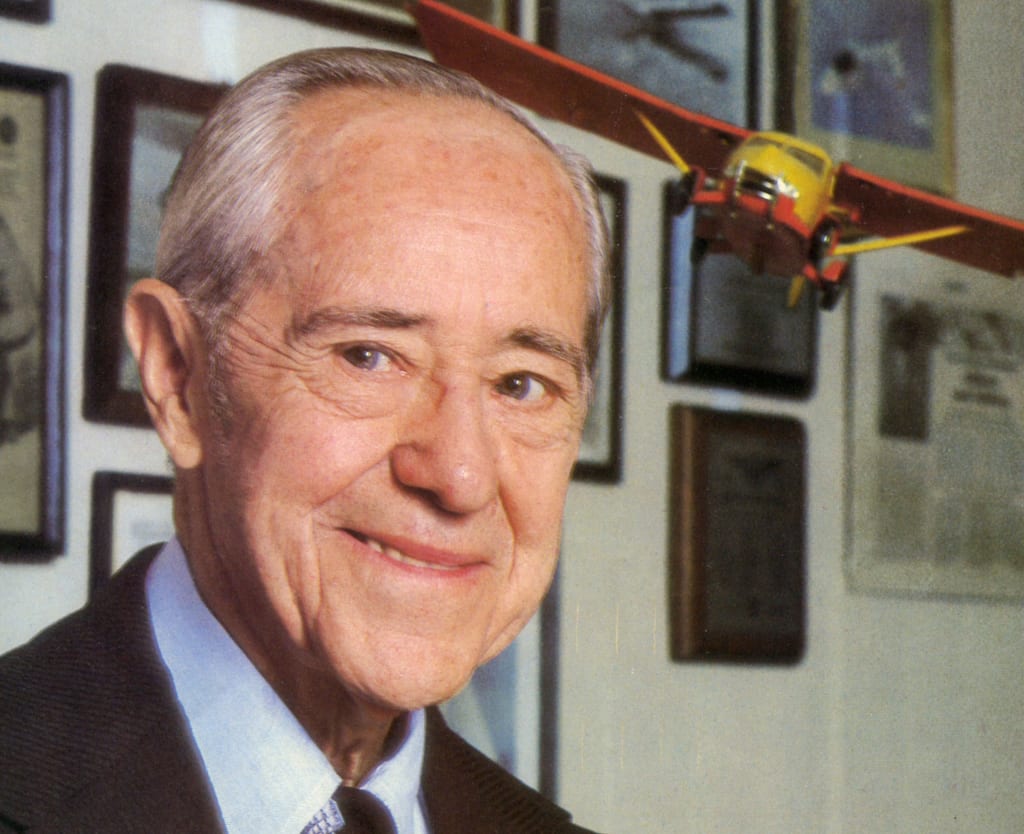

The last of Captain Barnaby's aviation impressions was when he worked at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pa. as the curator of aeronautics, where his job is to preserve all the notebooks and artifacts bequeathed by his old friend Orville Wright to the Institute at his death in 1948. The then 85-year-old Barnaby was interviewed for OMNI in 1978 by fellow Early Bird pilot Paul Garber, historian Emeritus of the National Air and Space Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Image of Ralph Barnaby

Q: What did you think of the Wright brothers?

A: They were wonderful men. And very fortunate in their choice of parents. Their father was Bishop Wright of the United Brethren Church. He was a very strict man and a man of definite principles and religious beliefs. Yet he felt that his boys should do what they wanted to do. They would come to him and say "I want to buy a bicycle." And he would say "Okay. When you have earned enough money to buy a bicycle, you buy a bicycle." He told them they could do anything they wanted, as long as they found the money to do it with. He wasn't going to finance them. And, as a matter of fact, that was one of their great characteristics. One of the biggest mysteries in aviation was that no one could find out who was financing the Wright brothers. Who was behind them? The truth was they never accepted a penny from anybody. Their bicycle shop supported them.

Q: I understand that the cost of the Kitty Hawk flier was less than a thousand dollars. including round trip tickets from Dayton, Ohio.

A: That's true. And yet a few years ago the Air Force Association wanted to have a replica made for the Kitty Hawk memorial. They canvassed the big aircraft companies, and the lowest bid they got Was One million dollars.

Q: What do you think was the most important factor in the Wrights being the first to fly?

A: Well, I think Wilbur Wright stated it very well in one of his early letters in which he says that man already knows how to build structures light enough and strong enough and with wing area enough to support them in the air. We know how to build power plants light enough, powerful enough to drive the structures through the air. The thing we don't know is how to control them in flight. And on top of all that, there isn't anyone who knows how to fly. It's interesting to note that the Wright brothers, of all their predecessors, all the men who tried to fly before them, were the only ones who were skilled pilots and had several hours of flying with the control system they invented. That was the secret. They had to have a three-axis controlling system pitch, yaw and roll. They developed all of that and got in hours of flying with the system before attempting to fly their airplane.

Q: They got in their practice by . . .

A: Gliding. An important thing to me—as a prime-interest glider man—is that the Wright patent was applied for in May of 1903, about six months before they flew the first airplane. In other words, that three-axis control system was worked up entirely through their glider experiences. They would make as many as 200 flights a day. And it wasn't so hard because at Kitty Hawk they were flying under conditions that no man had attempted to fly under before. They were flying in twenty- and thirty-mile-an-hour winds, which meant that they could go up and make a flight of two or three minutes and set down practically where they had started from Just hovering there. Soaring, actually. So the job of getting it back up the hill wasn't such a problem. I can imagine Lilienthal [Otto Lilienthal, the German aviator who made 2000 glider flights in the late 1800s] gliding off that big mound he built in Germany And making a flight down, lasting three, four five, or six seconds. And then it would probably take him half an hour to drag the glider back up the hill again to make his next flight.

Q: When did you first meet the Wrights?

A: In October 1910, at the second International Air Race. It was held on Long Island, at Belmont Park. The same place where Seattle Slew won the Triple Crown.

Q: The airplane of the Wright brothers then was the Baby Grand, wasn't it?

A: That's right, the Baby Grand. I was seventeen and told my high school teacher Mr Small that, that particular week I probably would not be in school. And he said, "What's the matter? Family trouble?" | said no. was going to the air races. He said, "Oh, you are are you?" I said. "Yeah." And he said, "Could go out with you?" So he went with me to Belmont Park. I spent most of my time there at the Wright hangar.

Photograph of the Wright Brothers c. 1908

Q: The airplane of the Wright brothers then was the Baby Grand, wasn't it?

A: That's right, the Baby Grand. I was seventeen and told my high school teacher Mr Small that, that particular week I probably would not be in school. And he said, "What's the matter? Family trouble?" | said no. was going to the air races. He said, "Oh, you are are you?" I said. "Yeah." And he said, "Could go out with you?" So he went with me to Belmont Park. I spent most of my time there at the Wright hangar.

Q: What was your connection with the Wrights?

A: My brother, who was a mechanical engineer, worked for the American Bosch Magneto Company. And they got the contract to make the eight-cylinder magneto [the device that supplies electricity to the spark plugs] for the Baby Grand. He took the magneto out to Belmont Park and installed it and was there the whole week tuning it up. He took me along with him. I was one of those "hand me this: hold on to this: fetch me that" for the Wright brothers.

Q: The Wrights didn't win that race, did they?

A: No, but the Baby Grand had a speed of eighty miles an hour when Orville test-hopped it. That would have been faster than anything else entered. But Orville didn't race the Baby Grand. They had one of their top pilots, Walter Brookins, do it. He came by the grandstand about a hundred and fifty feet high when the engine sputtered and quit. He put the nose over in a steep glide and went down. The plane hit and rolled end over end, wrapping the tail around it and leaving Brookins lying in the field behind it. He lay there for a few minutes and people started to crowd out into the field. Then Brookins got up and waved. He started walking in toward the grandstand, took about five steps, and collapsed. They took him away in an ambulance, but he wasn't badly hurt.

Q: How were the two Wright brothers different from each other?

A: Wilbur was the more aggressive of the two. He was the spokesman, generally. He was more outgoing. My only personal knowledge of Wilbur, though, was that one week. I never saw him again. Because it was in 1912 that he died.

Q: On May 30, of typhoid fever at home in Dayton, Ohio, in bed.

A: That's right.

Q: Orville Wright was a shy man?

A: Orville had very little to say at that time. Oh, he talked normally. But he was very reticent when meeting people. He didn't seem to enjoy it very much.

Q: You knew him until his death, didn't you?

A: Yes, I knew him quite well. I used to see him often in Washington [DC]. I got best acquainted with him on the annual jaunts to Langley Field. They used to hold sort of an open house once a year. The most fun was the night boat from Washington to Point Comfort. We'd all be on for dinner. And there was one table that would be Orville Wrights. And Tony Fokker would be there . . .

Q: Of Fokker Aircraft?

A: Yes. A whole gang of us. Now I said that Orville was very reserved. He was with people he didn't know. But with a gang like that he could be most garrulous and full of good stories. He talked his head off. Then afterwards we would adjourn to the center of the ship, where they had this big piano and we'd have a songfest. Orville loved that. He didn't sing himself, but he would sit there and rock, tap his foot, and have a wonderful time. The last time saw Orville was on One of those trips–summer of '47. He died in January the next year. But perhaps the closest got to Orville was when was stationed out in Dayton in 1928 and 29’. Saturday afternoons he would hold open house, with sandwiches and milk or lemonade. People would drop in—mostly officers stationed at Wright Field. It was there he told me the actual blow-by-blow story of the crash at Fort Meyer. Virginia, where he was attempting to convince the Army to use his plane.

Q: You're speaking of the death of Lt. Thomas Selfridge, in September 1908?

A: Yes. Selfridge was riding as an observer. Orville was the pilot. He told me that they had to put a larger propeller on. He was going to take George K. Sweet, a Navy man, and he was pretty big, so they needed bigger propellers. But in the meantime, Selfridge had received orders sending him away the next day and he was scheduled to be the next passenger after Sweet. So Sweet graciously said, "Look, I'm not going anywhere. You take my place." So Selfridge made the flight that Sweet was supposed to make. Orville said that after they got off. On the first turn, he heard this clicking and he didn't know what it was. It was a tip of one of those big propellers hitting one of the braces that ran from the wing part to the tail. When he'd make a turn there was enough spring in the tail so the rudder would push it to one side and that would make the wire on that side go slack, and it would start flapping. The propeller would hit it and just tip it. Finally on this one turn—apparently it was a fairly steep turn, pretty well banked—it got enough slack so the propeller actually cut the wire. That was one of the wires that stabilized the whole tail structure, and it sort of twisted . . . and he had no control over either rudder or elevator. He just went in, Orville was seriously injured. Selfridge died.

Q: Speaking of happier times, it was you who broke Orville Wright's long-standing ten-minute gliding record set at Kitty Hawk in 1911.

A: Nine minutes and forty-five seconds. Yes, it was the Summer of 1929. I was just trying to get my certificate at the Cape Cod Glider School. already had my A and B certificates. For the C, the soaring certificate, you had to stay above the altitude of your launch point for five minutes. So they launched me in a glider called a Prüfling from Corn Hill on the bay side of the Cape. I started Cruising up and down the ridge and | passed the required five minutes. Then began thinking of that nine minutes and forty-five seconds so I kept on until passed fifteen minutes.

Image of early 20th Century glider plane

Q: Your first love has always been gliderS?

A: I was never particularly interested in engines. The fewer engines a plane has the more I like it. That's why I like sailplanes. After all practically all forced landings are due to engine failure. But a friend of mine once told me, "Flying a glider is like having engine failure before you take off." On the other hand, that's the safest place to have an engine fail.

Q: Tell us about your most spectacular glider flight --the 1930 launch from the dirigible Los Angeles.

A: I did that for Admiral Moffett, the first Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. William Moffett was a great public relations man. He found that in order to get money out of Congress you had to do things, startling things. And so he sent for me one day and said, "Barnaby do you think it would be possible to launch a glider from a dirigible, from the Los Angeles?" I sort of drew a deep breath. He said, "You don't have to answer me now It's just an idea had. You think it Over and come in and see me tomorrow let me know what you think. But think it over carefully because if your answer is yes, you're going to do it." | didn't sleep much that night. The next morning finally got myself unscrambled, and I said, "Yes, Admiral Moffett. I think it would definitely be possible. And I'll do it, with a couple of conditions." "What are they?" he asked. "First Of all." | told him, "I'd like to use the Prüfling glider that flew to establish my record up at Cape Cod. The second is that go to Lakehurst [the New Jersey airship base] and supervise the installation of the release gear and the holding of the glider and all that." Moffett just said, "That's easy"

Q: Why were you concerned about the release mechanism?

A: I wanted to be sure was going to be held by a single release instead of a double. This business of trying to let go of two releases at the same time is a little hard. Take a rubber band and stretch it out with both hands and try to let go of both ends at the same time. You can't do it. It's going to shoot off this way or that. So we devised a Single hold using a bomb release, which we installed under the belly of the Los Angeles. They put it right over where the cockpit was to be. They had made a hatch so I could transfer from the airship to the Prüfling while we were airborne.

Q: And the whole thing was just a publicity stunt?

A: Not entirely. See, the landing of one of these big airships was a drill all in itself. When you went into an airship base, there'd be a handling crew that would come out, take your lines, and bring you in. But suppose you had to make a landing somewhere, for some reason or another, where there wasn't a landing crew? Each airship carried a landing officer whose job it was, if they had to make a forced landing, to parachute down at the nearest town and to round up the police department, the fire department, the Boy Scouts, the chamber of commerce, the Rotarians—any number of people they could—and get them out and train them to handle the airship when she came in. Well, Moffett's idea was that they could send a landing officer down in a glider that could be released ten miles or so before they got there and go down and land at the airport. And he'd organize a landing crew right away. They wouldn't have to wait for him to come down in some field. That was the official reason he gave for it.

Q: Dropping a glider from a dirigible—it reminds me of the Space Shuttle test or the V-15 rocket plane being dropped from the B-52 bomber.

A: As a matter of fact, just before the first test launchings of the X-15, I was being interviewed on a radio program about engineering in aviation. And when I explained how they were going to take the pilot up in this thing with no motor and no propeller and drop him as a glider the announcer said, "Ralph, do you mean they're going to take this man up forty thousand feet in a plane that's never been flown before, cut him loose, and he's going to fly down?" And I said, "Yes." He said, "Gosh, I just can't imagine such a thing as that. Can you imagine what it would feel like to be sitting in that thing and listening to a countdown?" I said, "Yes ... I can ... I don't have to imagine. I can remember when I sat in the same position under the belly of the Los Angeles." He said, "What did you think about?" I said, " sat there thinking, "What am I doing here?"

Q: What was it like that day?

A: They woke us up at five o'clock that morning, January 31, 1930. God it was cold and dark. It had been warm the day before and ice had melted and frozen in the tracks of the big door and they couldn't get the airship out. They had to get torches, and it took an hour to get the doors open. Then they walked the ship out to the mooring mast, hooked it up and walked the mooring mast well out into the field, ran it out on its track. Then they brought the glider out, hoisted it up, and hooked it to the release. I rode in the control car of the airship. We went down the coast to Atlantic City and then back up the coast and came back in at 3000 feet toward Lakehurst. When we were fairly close, we rigged an aluminum ladder from the hatch down into the glider's cockpit, and climbed down. That to me was the scariest part. In the cold weather my hands were numb, and going down that aluminum ladder was wondering if there was any chance of the glider's busting loose while I was getting into it. When I was all set had them bring up the speed to forty knots. We were headed into the wind towards the approach end of the field because I intended to circle it on the way down. The captain started a countdown. He started with ten and at zero he cut her loose.I dropped like a flash. I wanted to be sure and get away from the airship because there were two big propellers ahead of me and three behind me. wanted to get down quick. I leveled off about fifty feet below the ship. From then on down it was duck soup. Except . . . the only thing was thinking of On the way down was a cup of hot coffee.

Q: Set any records on the way down?

A: The flight was only thirteen minutes. I didn't try for any soaring records or anything like that. The amusing part of it was that when I dropped away from the Los Angeles and became the great glider expert, my total glider time was about twenty-five minutes. And I hadn't flown anything in a year. I was busy pushing pencils around in the Bureau. They said, "Don't you want to take the glider out and do an auto tow or something to make a test run on it?" said, "I don't know I'm afraid might crack it up. If I'm at three thousand feet ought to be able to learn to fly it on the way down."

Q: Did you ever drop away from the dirigible Akron in a powered airplane?

A: No, I never did.

Q: I know that the Akron was the largest airship of its time and carried five fighter aircraft, and it seems to me that both you and Admiral Moffett were involved in its loss.

A: Well,I never dropped away from the Akron, but in a way, I was involved in the final disaster …

Q: When a hurricane-force Storm pushed it into the ocean off the coast of New Jersey in April 1933.

A: That's right.

Q: Only three survivors from a crew of seventy-six. What was your role in it?

A: Very indirect. I was doing sculpture at that time. I was working in the Bureau of Aeronautics and I wanted to do a bust of Admiral Moffett, who was due to retire in six months. He had seen my work and agreed. I told him he didn't have to pose, that whenever he had an hour of reading to do I would come up and work. He'd sit there reading reports or the morning paper and I'd put my calipers on his head for various things. When you start a piece of sculpture you establish basic points on the bust and measure from there to the tip of the nose and other places on the head. Then one day I told him. "Well, Admiral, as far as the likeness is concerned, consider this done. But I've got to dress you up, put on your collar and your shoulders, and finish that part. But that's easy. Sometime when you're in uniform– we only had to be in uniform once a month—if you could give me half an hour I could finish up the necktie and stuff like that. But one thing. I'd like somebody else to see it. So far nobody but you and I have seen this thing. I'm not qualified to say whether it looks like you, and I don't know if you are either. I get to working on this thing and after a while it gets to looking more like you than you do, and then I know there's something wrong." So he said, "Well, how about bring Mrs. Moffett in tomorrow?" So she came in looked it over and Said, " I think it's lovely. It's perfect. Don't change it. Finish it up. It's perfect the way it is." So I said, "Okay only need one more day to finish up the shoulders." The following Monday morning as was coming in ran into Admiral Moffett in the hall, and he was in uniform. And I said, "Oh, Admiral, how about letting me put on the finishing touches today?" He said, "Barnaby, I can't today. There's a car waiting down in front to take me to Lakehurst. I'm going out on the Akron." He never came back. He drowned that night. Out off Atlantic City.

Q: And the bust?

A: I took a mirror and put on my own uniform and finished the job. And had it cast in bronze for Mrs. Moffett. I took it down to the Naval Academy, where it's now in a niche at one side of the entry door there—a bust of which I'm very proud.

Image of General Billy Mitchell c. 1919

Omni: You knew General Billy Mitchell?

Barnaby: Billy Mitchell was a wonderful man, a man of great vision. But a man with very little patience. He was just imbued with aviation and felt that it was the military weapon, the coming military weapon. The trouble was things didn't move fast enough for him. He had many attributes of a great man. For instance, like many great men—and have known a number that would put in that class—he had a wonderful memory. He seemed to never forget someone he had met and talked to. I met him aboard ship coming back from France after World War I. I was just one small ensign, and he was there with his whole staff. Eddie Rickenbacker was there, too. But When I took my walk around the deck every day generally he would hail me and say "Come on Over and sit down, Barnaby." And he'd talk to me about the Navy and about aviation and what I planned to do. I told him I was going to stay in aviation and that had agreed to stay in the Navy for two years after I got home. I didn't see him again until almost a year later at a big aviation ball in November 1919. Mitchell saw me and addressed me by name even though he had seen me only four days on the boat coming back and talked to me maybe a total of fifteen minutes or so. He said, "I see you're still in the Navy" I said, "Yes, I've decided to stay in." "That's fine," he said, and we talked awhile. After that I saw him from time to time. I remember when they had the Lampert Committee hearings and he testified. That's When he blew his stack and made all the statements that upset everybody and led to his court-martial.

Omni: In 1926, for insubordination.

Barnaby: Yes. Of course, he did exaggerate in a way. He would say "We now have an airplane that can climb to thirty thousand feet, that can fly so many thousand miles and carry so much load. . . ." He led you to believe that there was One airplane that could do that. There wasn't. One could fly the miles, but do nothing else. Another could climb, and so on. He tramped on so many toes. I think if there had been someone who could have held him in check he would undoubtedly have been the first Chief of the Air Force. I don't think there was anyone else who could have touched him.

Omni: Well, the public favored his ideas— his demands for an independent air force separate from the Army and Navy and his encouragement of commercial aviation. And he had proved the effectiveness of airpower in those 1921 tests in which his bombers sunk three "unsinkable" German battleships. I remember that many believed the real purpose behind his conviction was to silence him for daring to attack our outmoded military concepts.

Barnaby: I was very fond of him. I felt very bad about it.

Omni: How well did you know Admiral Richard Byrd? You helped fit out the plane he took on his first arctic expedition?

Barnaby. He took only an amphibian, you know. We fitted that out. I met Byrd in Washington and worked with him on getting the equipment together.

Omni: How did you like him?

Barnaby: Ah . . . I never got to know him very well. I always thought he was kind of a Stuffed Shirt.

Omni: And what about Charles Lindbergh?

Barnaby: We met On various occasions. I think, finally, I met him enough times so that when I would run into him he knew me by name. But that's all. I won't say I knew him.

Image of Amelia Earhart c. 1930's

Q: Amelia Earhart?

A: A Wonderful gal. She was an excellent pilot. Bright. A brilliant woman. She was a woman I could have been very fond of, She, Orville Wright, and I served during the late Twenties and Thirties on a contest board of the National Aeronautİcs Association. We all got involved in a controversy over pilots who flew in an unsanctioned air race sponsored by one of the Chicago newspapers.

Q: She and navigator Fred Noonan disappeared in the Pacific in 1937. They were On a 27,000-mile round-the-World trip—the first such flight attempted close to the equator—and Were lost somewhere between New Guinea and Howland Island. But recently there have been the rumors that Franklin Roosevelt had really sent her on a secret spy mission against the Japanese. That her real target was a fly over of the Marianas or somewhere and that she was forced down on some Japanese island.

A: I do not believe it. I think she just went down. I've read the books on her and listened to her voice on the radio transmissions. First of all, they didn't have the equipment they should have had. And I don't think Noonan was a very good choice for navigator. And there is so damn much ocean. Now, I've looked at the map, and to go to Howland Island by way of the Marianas, where they talked about her going, would have strained her fuel level to practically zero. And I don't think Mr. Roosevelt would have asked her to do it. I can't imagine that. With all the naval aircraft and all the ships they had, why would he ask her to do that? It just is unbelievable to me. Well, lots of things presidents have done are unbelievable to me. That she would do it, realizing how close to the edge it was. . . . I don’t think so.

Q: Let's talk about one of your more recent exploits—your first prize in the Scientific American International Paper Airplane Contest.

A: Actually, that story began decades ago. In 1934 I was reading a British gliding magazine, and I saw they were holding a paper airplane contest. So I made one of my paper planes, put it in a cigar box—fixed the box up with cotton pads to hold it in place–and sent it off. It took second prize.

Q: And what kind of plane did you design for Scientific American in 1967?

A: It was identical to the one sent to England. Well, it was the same design, not the same paper airplane. I got much of my experience in these matters in the Twenties, when I was stationed at Wright Field. The Army still had some lighter-than-air officers out there, and in order to get their flight pay they had to fly in balloons. They couldn't just go for an airplane ride. So once a month they would inflate a gas balloon and three or four of them would go for a four-hour trip. The truck would just follow along. When their time was up, they would signal the truck that they were going to land and the truck would pick them up. Well, had always wanted to take a balloon flight and they always had extra room. So I used to go out riding. And to while away the time would grab a handful of paper and take it along. I'd fold up paper airplanes and turn them loose. It's impossible to make one that will fly straight all the time. Ultimately they'll start circling. Well, as soon as it starts circling it's just the same as a balloon. It drifts along with you. We usually flew at around three thousand feet or so–nice, comfortable—we could talk to people on the ground. Gosh knows how many flights I made, how many paper airplanes I released. I never saw one land. They would disappear from sight before they got down. I watched some for twenty minutes, still circling around down underneath. But it's a lot of fun to watch them. Also, you develop quite an eye for getting the plane absolutely symmetrical, the two rudders just the same and everything.

Q: Did you make paper airplanes as a young boy?

A: Yes, in the summer of 1908. My father [a mechanical engineer] had just opened a consulting engineering office down on Broadway, near Wall Street. And that summer I worked for him as office boy. It was a one-man operation, and he was out a great deal when he had jobs to do. And I answered the telephone. I had plenty of spare time, and read the daily newspapers. It was during that summer that we began to hear about the Wright brothers. Wilbur had gone to Europe to fly Orville had taken the airplane down to demonstrate it at Fort Meyer. So I read the newspapers and anything could get on aviation because the bug bit me immediately. That was also the beginning of my paper airplane work. I had an unlimited supply of eight-and-a-half-by-eleven-inch business paper my father's stationery that I could use to fold up. I began with the conventional dart and then started developing others. But what developed principally was my desire to get into aviation. Up to that time had been headed toward an art career.

Q: What formal art training have you had?

A: During the years 1907 and 1908 I was an evening class student at the Art Students League in New York City. I was in the antiques class, where you worked with charcoal, copying Greek sculptures.

Q: You yourself sculpted the large bronze commemorative plaque of the Wright brothers erected at Kitty Hawk and dedicated on the sixtieth anniversary of their flight in 1963. When you made that plaque, what did you work from since Orville was no longer alive and Wilbur was long gone?

A: Well, lots of photographs. I’ll never forget the dedication in December. The general topic of conversation that day at Kitty Hawk was "Why did they have to pick December 17?" It was bitter cold. The temperature was around twenty think. And a raw wind was coming in off the ocean.

Q: Now that you've seen the entire panorama of seventy-five years of flight, what is your reaction to the Space Shuttle?

A: Well, think if there's ever going to be any traffic back and forth into space– especially travel between space capsules or space workshops or things of that kind–you have to have a reusable shuttle. I wouldn't venture to say anything about interplanetary space travel, but it seems to me that you can't wash the baby down with the bath water every time you want to go somewhere. It is just too costly, regardless of how much wealth we have. But . . . I admit that my insight into the future has never been too good. I can't see that far.

Q: When you say you "can't see that far," you're speaking literally aren't you?

A: I've had some trouble with eye charts in my time, yes.

Q: So much so that despite having built and flown your own glider at the age of sixteen the Navy held off giving you your wings for many, many years.

A: Yeah. And in fact I almost didn't get in the Navy at all, thanks to the physical.

Q: That Was in 1917?

A: Right. I had applied to the U.S. Naval Reserve Flying Corps. I was told to report to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for physical examination and induction. I went in to see the medical officer, and it was the same old routine: "Take off your clothes. Stand over there on the scale." I weighed a hundred twenty-six pounds. "That's underweight. One hundred thirty is the minimum. How tall are you?" This thing slides down on my head. "Five feet four and a quarter. You're under height, five feet six. Stand over there and read the eye chart." I couldn't read it. “Out." So I walked out and went away. About three weeks later I got a letter from the Navy, bureau of navigation, saying, "Your request for waiver of your physical defect has been accepted. Report to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for induction." I hadn't requested any waiver. thought when they said they didn't want me they meant it. So I went back over to the Brooklyn Navy Yard with my letter and slapped it down on the chief's desk, and he looked at it and said, “Take it into the doctor." I went into the doctor: he read the letter and said, "Just what was your physical defect?" I Said, "Damned if I know." I Wasn't going to give him any information. He said, "Well, there's no need of my giving you an examination. Whatever it is, it's Waived. Hold up your right hand." And I was in the Navy.

Q: But you were still denied your Navy wings for years because of your eyesight.

A: Yeah. I had one eye that was twenty-eighteen the other was twenty-thirty You had to be twenty-twenty. Even so, I was flying all the time as copilot, especially during the 1930s. Back in those days, in order to get flight pay, a military pilot had to pilot four hours a month. And if there were two aviators in the plane they had to split the time. You would get two hours; I would get two hours. Well, not having my wings, was very much wanted as a copilot because could do my share of the flying, but the other guy would get all the flight time. After a lot of flight time—hundreds of hours, I would say—l finally talked the Admiral into at least giving me flight pay. But still no wings. Later Commander Jimmy Schumacher at Pensacola [Florida] invited me down to teach a glider course, with the chance that I might be able to wangle myself wings at the same time. So I went down and ran the glider school on weekends. At first we just trained instructors. But then I started doing a lot of glider flying myself, and any time there was an air show, I always put on a glider exhibition. I'd go up to three thousand feet, do a few loops and spins, and come in and make a spot landing. I'd taxi right up, park the glider right in the line—in the row of other airplanes there. As soon as I'd get out I'd go over and say to the doctor "Goddamnit, you know I can fly. You see me flying every day." And he'd always say, "The rules say you have to have twenty-twenty eyes."

Q: So how did you get your wings?

A: Tonsillitis. I came down with a bad case. The doctor took a look at me and said, "Barnaby, I'll tell you what I'll do. You let me take your tonsils out, and I'll write the waiver on your eyes." I said, "Sold!” So I had my tonsils out. That's how I got my wings. I was over forty-four years old when started flight training.

Q: One final question. If given the chance, would you like to fly on the Space Shuttle?

A: I would like to be, say, fifty years younger and do it. Yes. No. I don't know. Was it Oliver Wendell Holmes who in his last years, when a young lady walked by, said, "Oh, to be eighty again!"? I would want to be a little less than that, when you talk about these Space Shuttles. I think maybe I ought to be thirty again. But right now . . . I've done enough.

About the Creator

Futurism Staff

A team of space cadets making the most out of their time trapped on Earth. Help.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.