China's Environmental Cooperation

Paul Kingsnorth's The Dark Mountain Manifesto attributed climate change to china's ongoing economic and geopolitical problems.

Ask a Westerner what most surprised them about their trip to China. If they were not staying in a five-star hotel in a major city on the dime of a major Chinese corporation, most likely you are going to get your ear bent with stories of people spitting on the floor of, not just a public streetcar, but their own bloody offices!...and also of pollution that makes L.A.’s ring-around-the-collar skyline circa the smoggy eighties look like a Rocky Mountain High by contrast. The brute summary is that this place is colossally productive, and also colossally filthy—and unashamed of it.

The UK Guardian writes of an epic, and superbly utopian, initiative on the part of Chinese banking—the “Green Credit Initiative”. The notion is that before a loan is given, the environmental impact of what the loan is creating has to be investigated, and then “rigorously monitored.” Sounds fantastic. The maybe-biggest and fastest-growing economy in the world is going to police where its credit flows to in future, and seeks to make it as green as possible?

Only…not. A group of Ecuadorian environmentalists wrote to six of the biggest Chinese banks to protest the opening of an Ecuadorian copper mine whose injury to the surrounding landscape will be catastrophic. The response? No response.

There was an ask to get the Spanish-language letter translated into Mandarin. Then, after that happened…no response.

President Obama has authored new carbon-emissions rules—non-dependent on the will of his Teabagger foes—that some environmentalists feel will have more teeth than any regulation since the Nixon era. It’s an okay start, but even if Obama makes more leaps and strides, will it matter at all in terms of our global fate if China won’t play ball?

One first catastrophe: China’s population is expected to grow from 1.3 to 1.4 billion people by 2050. Similarly, Indonesia, India and Brazil will have ballooning populations at even more dire rates. Let’s just start there: these increased populations coming online to our resource reserves are going to be an even more massive drain than we are experiencing now…and an even more significant number of polluters.

A second cataclysm: China may well not recognize any of our greenhouse-gas guidelines in their race to the economic top, in which case all the cuts, all the good deeds of the U.S. and Western Europe will be obliterated by what the Chinese don’t do. If they decide they really need coal-burning power plants, resist solar power, use fossil fuel burning for transport, or massive amounts of clothing and other goods built in smoke-spewing factories, all our virtuous actions are thrown out the window.

Lastly and perhaps most damningly: It is suggested that from the devastation of the fish supply to the paucity of breathable air, the Chinese may well have already committed irreversible damage. Injury that no amount of future good deeds can ever walk back.

What’s left? Despair? Well…kind of, yes. But there are some creative voices within the blackness of this terminal prognosis for the planet. Take a look at the brilliant environmentalist (or one-time eco-activist) John Kingsnorth’s brilliant Dark Mountain Manifesto.

Here’s a little bite of Kingsnorth’s genius: The pattern of ordinary life, in which so much stays the same from one day to the next, disguises the fragility of its fabric. How many of our activities are made possible by the impression of stability that pattern gives? So long as it repeats, or varies steadily enough, we are able to plan for tomorrow as if all the things we rely on and don’t think about too care- fully will still be there. When the pattern is broken, by civil war or natu- ral disaster or the smaller-scale tragedies that tear at its fabric, many of those activities become impossible or meaningless, while simply meeting needs we once took for granted may occupy much of our lives.

What war correspondents and relief workers report is not only the fragility of the fabric, but the speed with which it can unravel. As we write this, no one can say with certainty where the unravelling of the financial and commercial fabric of our economies will end. Meanwhile, beyond the cities, unchecked industrial exploitation frays the material basis of life in many parts of the world, and pulls at the ecological systems which sustain it.

Precarious as this moment may be, however, an awareness of the fragility of what we call civilisation is nothing new.

‘Few men realize,’ wrote Joseph Conrad in 1896, ‘that their life, the very essence of their character, their capabilities and their audacities, are only the expression of their belief in the safety of their surroundings.’ Conrad’s writings exposed the civilisation exported by European imperialists to be little more than a comforting illusion, not only in the dark, unconquerable heart of Africa, but in the whited sepulchres of their capital cities. The inhabitants of that civilisation believed ‘blindly in the irresistible force of its institutions and its morals, in the power of its police and of its opinion,’ but their confidence could be maintained only by the seeming solidity of the crowd of like-minded believers surrounding them. Outside the walls, the wild remained as close to the surface as blood under skin, though the city-dweller was no longer equipped to face it directly.

Bertrand Russell caught this vein in Conrad’s worldview, suggesting that the novelist ‘thought of civilised and morally tolerable human life as a dangerous walk on a thin crust of barely cooled lava which at any moment might break and let the unwary sink into fiery depths.’ What both Russell and Conrad were getting at was a simple fact which any historian could confirm: human civilisation is an intensely fragile con- struction. It is built on little more than belief: belief in the rightness of its values; belief in the strength of its system of law and order; belief in its currency; above all, perhaps, belief in its future.

I urge you to take a look at the rest. Kingsnorth bravely looks at: what might come next for us if all that we are used to—even in terms of the physical constituents of our day—suddenly collapsed? What would we do if, in fact, life did go on? It’s a question that may soon be urgently worth asking.

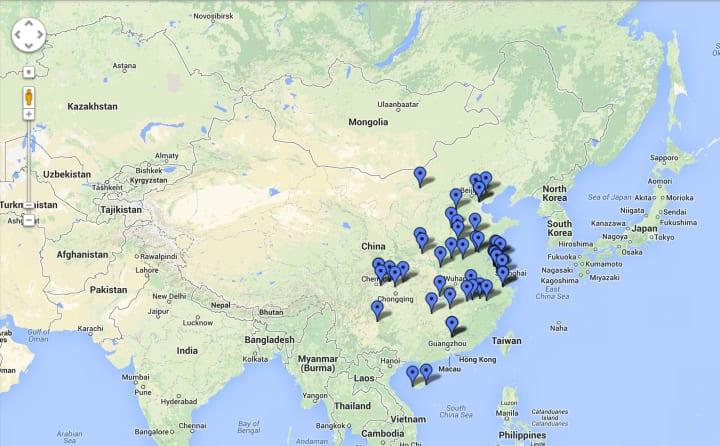

Top Environmental Issues Facing China

Environmental problems in China are getting worse and worse day by day. Rapid development has turned green fields into wastelands. Some parts of Shanghai are sinking because of excess groundwater use; other cities suffer air pollution and don’t even appear in satellite pictures. According to the report, only 32% of industrial wastes in China is treated properly. There are also big concerns about sulfurous clouds drifting to Japan and other countries. Chinese officials have just started to acknowledge the problem while people in the country have to face environmental catastrophes every day.

Air Pollution

via Telegraph

Environmental Protection Agency developed an air quality scale that measures the level of pollution. If the number is high, it’s unsafe to breathe and people are advised to stay at home and remain as motionless as they possibly can. However, every month the index in Chinese capital surpassed the 300 thresholds more than 10 times.

More than 5 million cars in Beijing, as well as an established manufacturing sector, make the situation worse by producing an extensive amount of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, ozone and other pollution. However, many experts see many coal-burning electrical plants as the main problem. China burns almost 50% of the world’s coal, the same amount that is used by all other countries in the world. All major cities are surrounded by networks of coal-burning plants. As a result, Beijing is one of the most polluted cities in the modern world.

Water Pollution

via RandRead

Water considered polluted when means that dangerous foreign substances, chemicals or metals are introduced to it. More than half of water in China is polluted to the point when it cannot be drinkable, and one-quarter is so dangerous that even plants cannot use it. Groundwater is also unsafe: 90 percent of it is polluted. However, more than 40% of farmland relies on it.

A major chemical accident happened in China in January 2013, when benzene leaked into the Huangpu River. 20 people were hospitalized; others had to drink water that was delivered by fire trucks. At the same year Chinese businessman, JinZengmin offered a $32,000 reward to an environmental official, who would dare to swim in a river nearby the Jin’s hometown. The river is heavily polluted, thanks to the local shoe factory. Nobody wanted to try. It illustrates that water pollution is a big problem in China today.

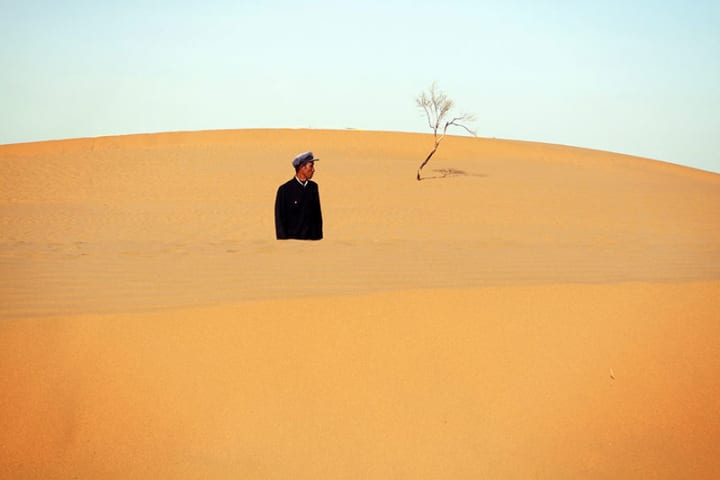

Desertification

Photo by Sean Gallagher

China owns 9.6 million square kilometers of land, but a huge part of it is subject to deforestation.

Massive conversion of forest into farmland makes heavy damage to forests of China. Desertification, or land degradation, goes hand in hand with deforestation. As a consequence, almost 2.6 million sq. km. of China is under desertification, which is almost a quarter of the country. As a result, the desert in the country expands every year by 2,460 sq. km. Moreover, desertification causes dust storms, eroded topsoil and mud-choked rivers.

According to Chinese desertification control officer, Liu Tuo, the country needs 300 years to recover. But now, many people have to leave their homeland because they can’t raise anything for food there anymore.

Biodiversity

via NY Times

Biodiversity, deforestation, and desertification always go together. As areas of forest are cleared, animals struggle to survive. The killing of tigers for their bones, rhinos for horns or elephants for ivory goes far beyond borders. China is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world; however, nowadays many threats affect the survival of many species.

Cancer Villages

Those areas in China that are adjusted to industrial networks have high rates of cancer. For years, people have been trying to force the government to address the problem of so-called “cancer villages”, or towns that are so polluted that living there is a cancer risk.

For instance, there is a river in Chinese city Shangba that flows through the town. It changed the color from white to orange because of industrial effluent. All fish died, as well as birds that drank from that river. Some of the contaminants there are known to cause cancer. As a result, 6 people also died.

In 2013 Chinese environment ministry published a report that noted that those chemicals that are banned in other countries are found in China.

Population Growth

China is home for almost one-seventh of the population of our planet. An emerging middle-class demand for goods that were once considered luxurious, such as red meat and cars. Nowadays Chinese people, that used to have a healthy diet, consume twice as much meat as Americans.

This trend that is followed by over a billion people has influence on the whole world: from liquor and sugar prices in Europe to climate changes everywhere.

Chinese government strives to achieve economic development at any cost. However, the environment ministry has agreed that pollution causes many problems to the country and its citizens. There is hope that Chinese government will do some positive changes concerning environmental issues.

About the Creator

Matthew Wilder

Writer-director of the forthcoming adaptation of Eddie Bunker's Dog Eat Dog. His first feature won its star Bill Pullman a Special Jury Prize for Performance.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.