A Tale of Two Star Wars

The Feeling Force versus the Thinking Force

The teaser trailer for the next Star Wars movie, The Last Jedi, slated for release on December this year, was quite underwhelming. A large part of the two minute trailer was either black screen or Lucas film logo, with Williams' lingering score pulling the nerd heartstrings in the background. There's a few lines of dialogue, a couple of action scenes, the obligatory Kylo Ren's red flaming crucifix lightsaber, some rather dull island scenes, and do we really need another pod race?

All of which highlights a fundamental contradiction coming out of the new Disney Star Wars universe. With the new trilogy, the emphasis is on nostalgia. The Force Awakens (#7 in the series), very likely The Last Jedi (#8) if the above trailer is any indication, and the 9th movie, have or will be retreads of the original trilogy. On the other hand, maverick new kid on the block, the appropriately named Rogue One, was so different in tone, storytelling, and worldbuilding to The Force Awakens and to what glimpses can be seen of The Last Jedi, that it doesn't seem to be set in the same franchise. I use the phrase "The Two Star Wars" to refer to this franchise dissonance.

The Two Star Wars controversy is reminiscent of the old "versus" feud between Star Trek and Star Wars, with each camp claiming their franchise has the more powerful weapons, or the better story. only now it's within Star Wars itself.

Ironically, this parallels the polarisation of Trek fans themselves between those who preferred the original and the reboot, with JJ Abrams again at the center of the controversy.

Within Star Trek, the Abrams reboot was so universally despised by hardcore fans that it was actually consigned to an alternate timeline, the Kelvin Timeline. Abrams himself is on record as saying he didn't even like Star Trek, and considered his own Into Darkness especially to be a mistake.

In the case of Star Wars, pro and anti Abrams opinion is more evenly divided; perhaps because Abrams was a fan of the original Star Trek, and genuinely wanted to honor it. Hence he did the opposite of what he did to Trek; instead of negating the original timeline, he cloned it. The teaser/trailer seems to imply that this will also be the case of the remaining sequels.

For the rest of this essay, I'll assume everyone has long seen both movies, so spoilers will not be a problem (if you live in an alternate reality and haven't, best to stop reading here). Along the way, I'll discuss science in science fiction, worldbuilding, and the psychological polarity of thinking and feeling

A Sentimental Reboot

It's the same story...

Star Wars: The Force Awakens, follows chronologically after Return of the Jedi, the last of the original trilogy, where the Rebels had destroyed the second Death Star, the Empire was crumbling, and a new era was beginning.

Except that it doesn't feel like a sequel. It feels more like a sort of Nietzchean eternal return, in which time loops around and repeats itself. Or maybe Groundhog Day.

A fascist totalitarian regime (the Empire, the First Order) rules the galaxy, but is opposed by a plucky band of rebels (Alliance, Resistance) led by Lea Organa. The bad guys have all the advantage of hardware and resources, equipped with massive star destroyers and TIE fighters, whilst the rebels wear orange and white pilot uniforms and fly X-wings. There's a young adult (Luke, Rey) stranded on a sandy world, where they own a fast hover ground-vehicle (landspeeder, Rey's homemade speeder) and are accompanied by a comical little droid (R2D2, BB-8). They realise their Force-wielding gifts when confronted and pursued by a black-masked Dark Jedi (Darth Vader, Kylo Ren) who in turn has an even more powerful and sinister master (Palpatine, Snoke). There's a young hotshot pilot (Han, Poe). A tentacled monster makes an appearance (A New Hope's Dianoga and Return of the Jedi's Sarlacc, now Han Solo's captured Rathtar). Most of the action takes place on three single-biome planets, desert, forest, and arctic (Tattooine, Endor and Hoth, in the original being replaced by Jakku, Takodana and Starkiller Base). There's a diminutive, bald, wrinkle-headed humanoid on the side of the good guys (Yoda, Maz Kanata). An important older male warrior father figure is sacrificed (Obi One Kenobi, Han Solo). The good guys are given the plans to a terrifying planet-busting superweapon (Death Star, Second Death Star, Starkiller Base) which nevertheless is destroyed with relative ease by the Resistance, thus saving the galaxy.

But sentimentality and worldbuilding don't mix

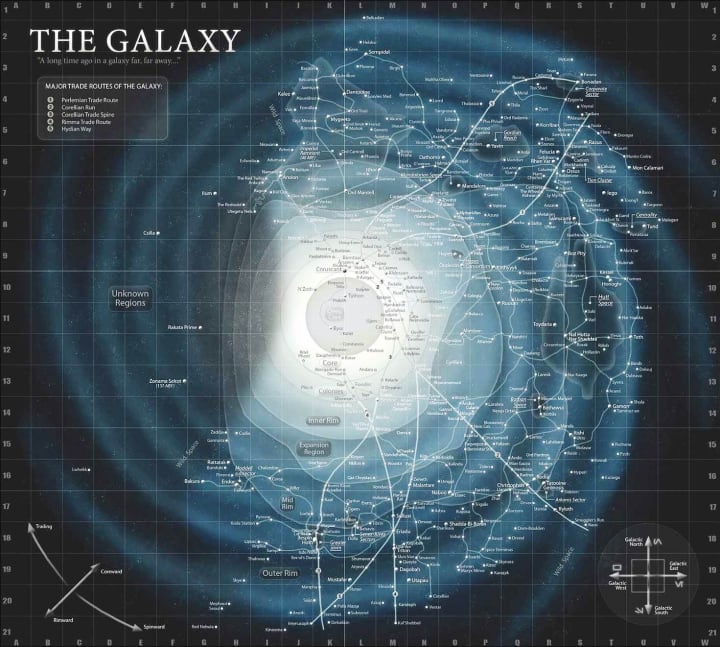

The Galaxy of Star Wars, an example of collaborative worldbuilding. From Star Wars, The Essential Atlas, by Daniel Wallace and Jason Fry (2009 Del Rey)

Worldbuilding is the nerd pastime par excellence. It is that aspect of the science fiction and fantasy creative imagination by which one creates an entire world or universe, with its own history, geography or planetology, biology, language, customs, politics, commerce, and anything else one might think of. Worldbuilding can be all about the background details and setting for a science fiction or fantasy story, or it can be a creative activity in and of itself, or a little bit of both. Science fiction and fantasy creators such as JRR Tolkien, Frank Herbert, Robert Jordan, George Lucas, Terry Pratchett, Peter Hamilton, David Weber, G.R.R Martin, and many others have managed to create astonishingly vivid universes in which their stories and adventures take place, and peopling these universes with various characters and races.

Both the original Star Wars trilogy and the follow-up prequels were rich in worldbuilding (this is so even if one dislikes the prequels), as were the collection of novels that constitute the the Expanded Universe (now relegated to "legends" and hence non-canon). The ultimate atlas of the Star Wars Canonical and Expanded Universe is Wallace and Fry's Star Wars, The Essential Atlas, shown above. This beautiful volume, with all its incredible detail, descriptions of planets, trade routes, and galactic history, has since been rendered obsolete by the decision (whether from George Lucas or not) to consign the entire Expanded Universe to the status of "Legends", which in this case means, even in the Star Wars universe, it's not considered real. All of which was to pave the way for the The Force Awakens and the two follow on sequels.

In re-telling the same story that Lucas did, there is no denying Abrams and his team recaptured the feeling and banter of the original trilogy in terms of directing, casting, acting, pacing, cinematography, music, and visual effects. But it makes no sense, in terms of an actual, imagined objective universe with its own historical causation, to repeat exactly the same events and characters forty years on.

The Force Awakens' science blunders

In The Force Awakens, Lightspeed is the same as aircraft speed

Of course, Star Wars is famous for its lack of hard science, so much so that some don't even consider it science fiction at all, but science fantasy (I disagree, but that's because I judge whether something is science fiction as opposed to fantasy is not it's science qualifications or lack thereof, but whether it uses technological tropes (spaceships, laser guns, androids, planets) or fantasy ones (dragons, spells, elves, alternate world continents). George Lucas for example was famously ignorant of science as shown by when he has Han Solo boast of “making the Kessel Run in 12 parsecs”. A parsec is not a unit of time, but the distance at which one astronomical unit - the distance of the Earth from the Sun - forms an angle of one arc second (or 1/3600th of a degree) or in other words 3.26 light-years. This leaves it to nerd fans to justify and rationalise this with refernces to black holes and curved space time

This situation is even more dire in The Force Awakens, due to Abrams' lack of understanding (or if he does understand, deliberately ignoring) the sort of scales of distance and speed that are central to space-based science fiction, as opposed to stories set on Earth, where distances are millions or billions of times less and speeds millions of times slower. When Starkiller Base activates its weapon and fires at and destroys the Republic capital in the Hosnian system, even though this is a "hyperspace beam" it can still be seen moving slowly above the stratosphere from a totally unrelated and non-adjacent planet, Takodana, a quarter of the galaxy away. It's as if the entire galaxy occupies a size no greater than a single planetary continent.

Another instance is how Han, on pilot reflexes alone, makes a landing approach at light speed to get past the shields around Starkiller Base, then slows down to a several hundred kilometer per hour for the obligatory aircraft style crash landing, despite the fact that the difference between light speed (10,800,000,000 km/h) and either crashlanding speed (say 200 km/h) or hovering motionless is irrelevant. It's as if light speed was the same as a aircraft cruising speed.

Brand New (and bleak) Story

Rogue One's protagonists are just as important in their own way as those of the major Star Wars trilogies. From left to right: Cassian Andor, Jyn Erso, K-2SO, Chirrut Îmwe, Baze Malbus, and Bodhi Rook

Godzilla director Gareth Edwards and writers Chris Weitz, Tony Gilroy, Gary Whitta and John Knoll built an entire storyline around a typically discussion of the Kessel Run sort. Why did the Empire make its ultimate superweapon, so vulnerable to a single well-placed shot?

Set between the events of the last prequel, Revenge of the Sith and the original Star Wars, A New Hope, it follows the tried and true Space Opera trope of a band of reluctant misfits who team up to steal the plans to the Death Star.

The movie itself had a difficult birth, owing no doubt to the Two Star Wars effect; its artistic incompatibility with the rest of the LucasArts and Disney stable. There were many reshoots, and large parts of the film were altered or cut, including scenes in the trailer that didn't even make it through to the actual movie

It tells the story of Jyn Erso, the grown, criminal daughter of enslaved Imperial scientist Galen. Pretending to go along with his captors in order to save his daughter's life, the elder Erso secretly works to undermine the planet-killing project from within. Knowing that her father holds the key to its destruction, a vengeful Jyn joins forces with Rebel intelligence officer Cassian Andor, reprogrammed Imperial droid K-2SO, blind spiritual warrior Chirrut Îmwe and his friend Baze Malbus, and former Imperial cargo pilot Bodhi Rook, to steal the space station's plans for the Rebel Alliance.

The story jumps from planet to planet with bewildering speed that, while disorientating, nevertheless give the feel of a vast universe and a genuine sense of wonder that one gets from good worldbuilding.

The settings are bleak, the story tragic, the morality more ambiguous, the characters insignificant and expendable in the grand swashbuckling scheme of galactic space opera. The whole tone is less like something from LucasArts and more like a more pessimistic but also more socially realistic space operatic universe. While the original team of misfits trope dates back to the epic action movies such as The Seven Samarai, The Magnificent Seven, and The Dirty Dozen, this trope easily adapts to scifi, in which morally ambiguous spacefaring misfits make do against oppressive regimes. Space operatic examples include TV shows like Blake 7 (one of the original British scifi rebels in a spaceship shows), Firefly, and Farscape, movies like Guardians of the Galaxy, science fiction books include J.S. Morin's Salvage Trouble / Black Ocean series, Becky Chambers The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet (about a group of outsiders on a spaceship, but not dystopian), and many others. Player-generated roleplaying adventure game characters also tend to gravitate to the misfit/outcast/orphan/rebel character. Indeed, these are very much the antiheroes, underdogs, and misfits that the pessimistic dystopian-loving nerd appreciates.

Ironically the moral ambiguity of Rogue One restores the same ambiguity in the original Star Wars concerning the "Han Shot First" controversy, where Lucas altered the footage, so that instead of the original movie where Han Solo pulls his blaster and shoots bounty hunter Greedo, Greedo shoots first, much to the disgust of fans everywhere. Perhaps in response to this, in the 2004 dvd version, the two shoot at the same time, but Han dodges. In any case, replacing the immoral Han with a family friendly one didn't go down well with fans. Rogue One however is even more amoral in tone because it isn't an isolated scoundrel but a large part of the Rebel Alliance itself. For example, unknown to Jyn, Cassian has actually been ordered, to kill Galen rather than extract him, and he is just using Jyn to lead him to him. Even here however there is the obligatory plot device that stops him doing this, so he and Jyn can be together as tragic lovers at the end.

Thinking and Feeling

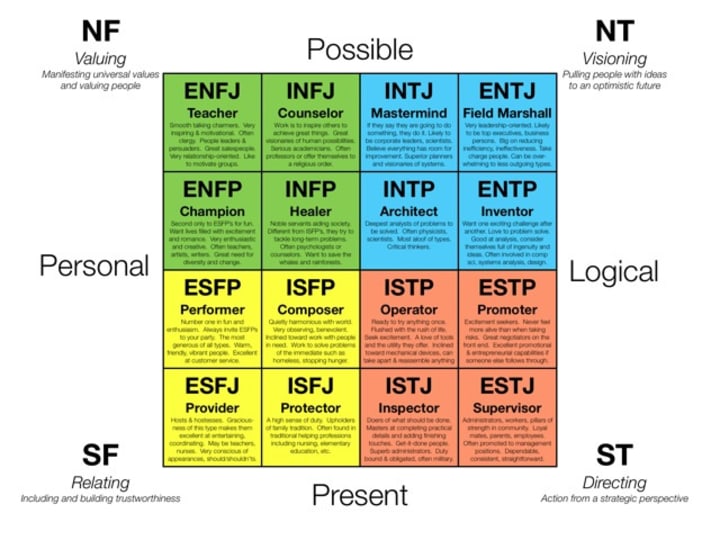

Jung's psychology typology as expanded by the Myer Briggs system (image from here)

The duality of The Two Star Wars is a result of a fundamental polarity and duality within in individual psychology. Two types of movies and two types of fans, can be described in Jungian terms, in this case as the Thinking and the Feeling personality type.

CG Jung was a Swiss psychologist and student of Freud who broke away to develop his own form of psycho-analysis, which he called Analytical Psychology but which is now called Jungian Psychology, which emphasizes myth and deep symbolism over Freud's emphasis on sexual repression, itself very indicative of the puritanical era in which the latter developed his theories of neurosis and the unconscious.

I have described the Jungian unconscious in relation to science fiction and myth in another essay (see Science Fiction as modern myth-telling). Here I'd like to consider another aspect of Jung's psychology, the ego and its types and functions.

What Jung called the ego isn't the colloquial definition. If we say someone's got a big ego it means they're narcissistic and full of self-importance. For Jung, the ego is the conscious personality, as opposed to the non-conscious aspects of the psyche, the Personal and the Collective Unconscious.

Jung divided the ego into four functions, which consisted of two pairs. These are the two rational functions of thinking and feeling, and the two irrational functions of intuition and sensation. Each of these represents a personality type. When one function is in the light of consciousness, the other is repressed. Hence the head (thinking) and the heart (feeling) will always be at odds.

Thinking and feeling represent the classic psychological polarity. The thinking type is the head-centered type, the lawyer or doctor, accountant or the scientist, considered with logic, ideas, rationality, and analysis. The feeling type is the heart-centered type, concerned with emotions, values, meaning, personal relations, and, well, feelings. The feeling personality type may work in human resources, in the service industry, or if creative be an artist.

One could go into other details, such as primary and secondary functions. For example, a thinking type may be secondarily sensation. But this sensation-Thinking type would be quite different, more practical in orientation, to the more imaginative intuition-Thinking function. There's also the way the consciousness energy is directed, whether inward (introvert) or outward (extrovert), all the various combinations here.

The Myer-Briggs test is a questionnaire designed to indicate psychological preferences. The foundations were laid by American educator Katharine Cook Briggs in 1917; around the same time Jung was developing and publishing his own typology. After the English translation of Jung's book Psychological Types appeared in 1923, she recognized the similarity of Jung's theory to her own, but also that it went far beyond her own work. With her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers, Katharine Cook Briggs worked on the during the War, and the first handbook was published in 1944. It has since gone through several revisions, and in the last few decades this typology has become extremely popular in self-help books and on the internet as a form psychological self-assessment.

The Myer-Briggs typology retains Jung's of thinking-feeling, intuition-sensation, introvert-extrovert typology, but ignores his compass of conscious vs repressed functions, and the distinction between primary and secondary functions. Instead offers a simple 16-category table by addition of a fourth pair of opposites, Perception and Judgement. These tables frequently appear on the internet, and are usually accompanied by little illustrations, or used to classify characters from nerd epics like Star Wars or Harry Potter, each type given a funky name, like The Provider, or The Supervisor.

How does this relate to The Two Star Wars? Well, the family friendly The Force Awakens, and doubtless the two follow-ups, is very much a scifi fantasy story pitched not just for nerds but also for norms, featuring as it does uncomplicated morality, larger than life swashbuckling heroics, an obligatory happy ending (Mostly. Han still bought the farm), and the bums on seats mass appeal of the norm-marketed movie.

It's pretty obvious to me that The Force Awakens is a Feeling-Perception movie. It appeals to sentimental feelings and recapturing the optimistic happy sense of wonder of watching the original Star Wars as a kid. There is almost zero thinking in it, as shown by the science fails. But neither are its fans nitpicking and judgmental. As perception types, they aren't too fussed about consistency or realism, and happy to suspend disbelief (and nerd judgmental criticism regarding lack of realism), to be entertained and have a nostalgic experience. The characters are all larger than life swashbucklers in a familiar bright and shiny universe.

Rogue One clearly is a movie made by nerds, for nerds. It just doesn't have the cheery family appeal of the usual Disney and Lucas fare. The gloomy setting appeals to the more melancholic and introvert NT and especially INTJ personality (christened the Mastermind in the Myer-Briggs typology, an appropriate name for a nerd type). Details such as worldbuilding, originality, scientific consistency, and minor characters, are things that are more important to creative writers, worldbuilders, and dedicated nerds Instead of focusing on the unattainable jock-powered people appeal of the Star Wars heroes, its extensive worldbuilding and obsession with getting all the little details of droid classification, sets, uniforms, and retrofuturism, approachable yet non-super-powered protagonists, and tragic storyline, it reminded me of the sort of bleak, dystopian scifi on deviant art or in self-published ebooks, and those fan made movies you see on YouTube, which sometimes are surprisingly more enjoyable and intelligently written than anything produced by the mainstream industry.

Nerd Heroes

A Star Wars droid who isn't a servile whimp. And a warrior fueled by wish-fulfillment.

In a mass-marketed "bums on seats" movie like The Force Awakens, the protagonists are outgoing, swashbuckling, and melodramatic. There are dogfights, lightsaber battles, and the protagonists themselves are so important to this universe that the entire Star Wars cosmos with all its trillions of inhabitants, revolves, Mary Sue fashion, around them. (The term "Mary Sue" referred originally to really badly written narcissistic Star Trek fan fic in which the female author avatar is the most appealing and competent character. It later came to mean any such infuriating overpowered author avatar characters; the male equivalent is sometimes called Gary or Marty Stu).

When watching these sorts of movies, be they Star Wars type science fiction or James Bond or any other action-adventure story, I sometimes wonder for example at the lives of the so-called mooks, those expendable underlings of the supervillian, who fall like ripe wheat before the hero's blazing guns (or swirling light sabre in the case of Star Wars). Don't they have a life, a family, people that care about them? Don't they ever want to one day do something amazing with their lives. Even if they're just brainwashed stormtroopers, that doesn't make them automatons. And what about all the other extras in the background of the grand stage the central heroes strut upon? The redshirts, the underlings, the cannon fodder, don't they have hopes and dreams as well?

This is where Rogue One comes in. Well, sort of. We actually now have a three level hierarchy. Mooks are still mooks, dying pointlessly in an uncaring universe, without even a movie to immortalise their sacrifice (they might get a YouTube fan-made video if they're lucky). Above them are middle grade characters, whose deeds and sacrifices and life and death are only in the background and periphery of the heroes story arc, the top level characters. These middle characters sacrifice their lives so that the Skywalkers and their friends can decide the fate of the galaxy.

Critics have mentioned that the Rogue One protagonists don't get the opportunity to shine in their own light. In part this is because they are confined to a single movie, not a trilogy or an HBO TV series. Even so, some of them are poorly drawn. The formulaic romance relationship between Jyn and Cassian is so dull and insipid the viewer doesn't even care what happens to them. Apart from one or two good lines, the defecting pilot Bodhi Rook comes across more as the comical sidekick. But two characters who really stand out are the snarky droid and the blind monk.

The tall, hulking, K-2SO is in striking divergence from all previous Star Wars droids. Star Wars droids are universally presented as mere property whose life and sentience amounts to nothing. When they do feature as major supporting characters, their character seems to be either childlike (R2-D2, BB-8) or obsequious and whiny (C3P0), and they only have a personality among themselves, as with the Abbot and Costello team of R2-D2 and C3P0, in which each needs the other to bring out his own personality.

How different is Rogue One's K-2SO from every other droid in the Star Wars universe! He requires no robot companion, and holds his own even among humans who considered him less than nothing. Considered less than a slave, he isn't even given the respect of being allowed to carry his own weapon. Yet he carries the mission through to the end, with courage and selfless sacrifice befitting the greatest human hero.

Then there's the blind warrior-monk Chirrut Imwe. While his friend Baze is the standard big guy/tank trope, it's the earnest Chirrut, who, while lacking force powers himself, constantly repeats the mantra "I am with the Force and the Force is with me" in a sort of wish fulfillment that almost comes to true, and that the viewer really wants to come true.

Characters like K-2SO, Chirrut and Baze, and Bodhi Rook, are support characters even in their own movie; insignificant and forgotten in the larger, uncaring universe of the trilogies. Yet their courage and integrity shine through right to the end.

Summing up

Two Star Wars, two sets of heroes, two types of story.

With the appearance of Rogue One, the Star Wars universe is no longer a monolith. There is now not one, but two Star Wars, each the polar opposite of the other, apart from being set in the same universe, and - in marked departure of the male-dominated (Princess Leia and the early Padme excepted) original trilogy and prequel - centered on a strong female protagonist.

The Force Awakens was, and its two sequels doubtless will be, a feeling-orientated, sentimental, nostalgic, conservative star wars, not only harking back to but literally rehashing the original trilogy. Not a parallel timeline reboot like Abrams Trek, but a literal retread of the original.

But for all this it worked, propelled by marketing, fan nostalgia, and the Lucas/Disney Star Wars brand it did great at the box office, both among fans and audiences new to star wars. It wasn't the movie the hardcore fans were expecting, but was still well received by them. I remember at the time on the Facebook Space Opera forum there was almost (with only a few exceptions) unanimously approval. But raise this topic now, once the buzz and the hype has worn off, and the approval is probably less than half.

Rogue One conversely is the classic polar opposite; a bleak, fastidiously accurate story of a bunch of misfits and outcasts. If I ever was going to write the story for a Star Wars movie (which I wouldn't, but only because it's more fun to play in one's own universe than in someone else's, and not because I don't love the franchise) I expect it would look very like Rogue One.

For this reason, it is pointless to ask which of the Two Star Wars is better. It's like saying, which is better, the feeling function or the thinking function. Both are an equally one-sided, yet also an equally necessary part of human nature. The Two Star Wars articulate this fundamental polarity in the human condition, as well as being two very different types of storytelling.

About the Creator

M Alan Kazlev

Imagineer, pantheist, essayist, vegan, nerd. Work in progress Freehauler Alcione, a dystopian social satire meets metaphysics space opera.Also teahing myself Blender so I can create scifi art for my stories

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.